A CLEVER SUBVERSION WHICH CHALLENGES

SOCIETAL & GENDER NORMS – ADITI YADAV

REVIEWS EMI YAGI’S NOVEL

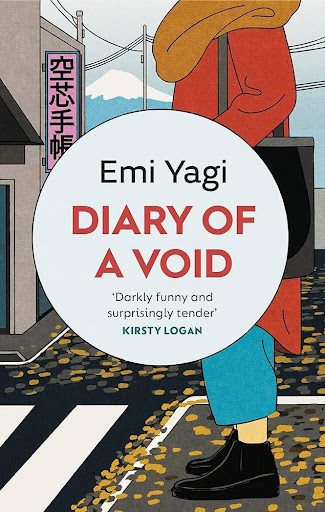

Title : The Diary of a Void

Author : Emi Yagi

(Tr. David Boyce & Lucy North)

Genre : Fiction/Novel

Language : English (translated from Japanese)

Publisher : Harvill Secker/ Viking

Year : 2022

Pages : 224

Price : INR 1590 (Hardcover)

ISBN No : 978-0143136879

Editor’s Comments. One of our prolific reviewers, Aditi Yadav takes a closer look at Emi Yagi’s novel, premised on its protagonist creating a clever subversion, reminiscent of Vidya Balan’s character from the Bollywood film Kahaani (2012). Ultimately, both raise similar concerns – what would it take for society to treat women and their bodies with a modicum of respect? And more importantly, what are the ways in which the ill-treated, female body can upend and challenge existing societal power relations.

Life on earth can be an exhausting enterprise, more so if you happen to be a woman. When you confront the harshness of gender roles and societal expectations, womanhood can feel like a relentless, fulltime job that’s also an impediment in realizing your real human potential, filling you with an emptiness that drives you to desperately to look for an escape. Emi Yagi deftly narrates this bitter reality in her novel The Diary of Void with ample humor, satire and surrealism. Yagi’s debut novel which won the Osamu Dazai prize has been lucidly translated from the Japanese by David Boyd and Lucy North.

The protagonist of the story, Ms. Shibata, is a young woman working for a company in Japan. The attitude of her coworkers and the chores she is expected to do in the workplace, paint a sorry picture of an average female kaishain (company worker) in Japan. She works late into the night, endures sexist remarks, attends post-work nomikais (drinking parties) against her wishes, serves coffee during official meetings, and cleans up after her male co-workers. Although the old Japanese custom of having ochakumis where the female workers poured tea for the male workers is not practiced anymore, the novel cleverly brings out the gender role expectations entrenched in the Japanese psyche.

The discrimination also seems evident in the menial tasks she’s asked to do – make photocopies, refill cartridges, answer phone calls, manage messy garbage situations, and so on. How does one confront this toxicity? When asked to clean up the coffee cups for the umpteenth time, Shibata’s pent-up anger makes her concoct a lie: she tells her coworkers that she is pregnant.

One casual, harmless lie and everything changes around Shibata – “So this is pregnancy. What luxury. What loneliness.”

She gets to return early from work, shop for groceries, and is greeted with extra care. Nonetheless, the misogyny doesn’t die down. Shibata senses her co-workers gossip about how she chose to be a single mother, some are curious about the gender of her (fictional) child and even have the nerves to say ,“You’re just not the type who would have a boy, Shibata … It’s going to be a girl.”

Shibata has to stay on her toes to conceal her secret. She innovatively wraps stuffing around her stomach to adjust the shape of her belly. She follows an app that tells her the size of the fetus corresponding to the week of pregnancy by comparing it to some fruit. She has more time for herself now – to eat, exercise, relax and enjoy. One can’t help but empathize with the eternal burden of womanhood that Yagi brings out through the story, as Shibata communes with Mother Mary on a Christmas Eve,

“I’m sure you were totally freaked out when they told you that you were pregnant, but at least your baby’s birth is now celebrated all around the world! And so many people have been saved by you, and by your child! Then again, to be eternally known as the Virgin Mother, as if that’s the only thing that gave meaning to your existence… Hey, did you have any hobbies of your own? Or maybe there was a singer you were really into? You must have gotten stressed out sometimes. I mean, being called the Virgin Mother, even after your son was all grown up…And then to have him crucified like that. I can’t imagine how hard that must have been. I just hope you managed to live your life the way you wanted, to take naps when you felt like it, to know yourself by a name that made sense to you.”

Shibata joins Yoga classes for pregnant women and expands her circle of female friends. She realises how other females also have a hard time given the apathy of their husbands, struggles with eating, and maintaining their bodies and raising kids. A particular passage is poignant,

“And there are a lot of people—husbands, parents-in-law, even your own parents—who say horrible things that make you want to say, ‘Fine, let’s trade places.’ But they can’t. They can never take your place. They can’t even understand you. Because they’re not you. I mean, I’m standing right here with you, Hosono, and there’s no way for me to really get how depleted you are, how exhausted.”

The novel’s chapters run as week-wise chronicles of Shibata’s false pregnancy. Yagi’s innovative literary construct, stems from Japan’s Boshitecho, which is a pregnant woman’s official record of her visits to doctor that also serves to journal of her pregnancy journey. The translators’ notes also explains how the Japanese title of the novel, Kūshin techō is reminiscent of this journal, where ‘empty core’ replaces child and maternal health.

However, Yagi’s surreal climax has the reader second guessing if Shibata was faking the lie itself. Despite the veracity of her account, or lack thereof, the story speaks for billions of women across the globe – how their body’s anatomy has defined their gender roles, leading to an oppressive and discriminatory world around them in family, workplaces and society at large.

Specifically in the Japanese context, the novel provides insight into why despite being the world’s third largest economy Japan ranked a dismal 116th among 146 nations in a survey conducted by World Economic Forum in 2022. The gender discrimination and lack of sensitivity to provide for institutional systems that would help women maintain work-life balance has had far reaching impact. The country is facing constantly declining birth rates, and recorded a historic dip in birth count, well below 8,00,000 in 2022. This is not only attributable to the historical burden of patriarchy in society, but also indicates under-representation of women in decision making platforms.

As former Japanese Minister of gender equality and children’s issues, Seiko Noda, rightly pointed out how Parliament has been traditionally dominated by “people who do not menstruate, do not get pregnant and cannot breastfeed”.

Shibata’s lie is an audacious act against the prevalent system that finds hard to acknowledge a woman as an equal human. How she stands up for herself and cleverly paves a path to find an escape is inspirational. But easy-to-pull-off-at-work personal rebellions in a work of fiction may translate into something Herculean for women of the real world.

Would it ever be possible, I wonder. Wouldn’t they just write it off saying, Hercules wasn’t a woman after all. None the less, Viva la Resistance!

■■

Author’s Bio:

Aditi Yadav is a public servant from India. She is also a South Asia Speaks fellow (2023). Her works appear in Rain Taxi Review of books, EKL Review, Usawa Literary Review, Gulmohur Quarterly, Narrow Road Journal, Borderless Journal and the Remnant Archive.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates