By Smita Sahay

Editor-In-Chief

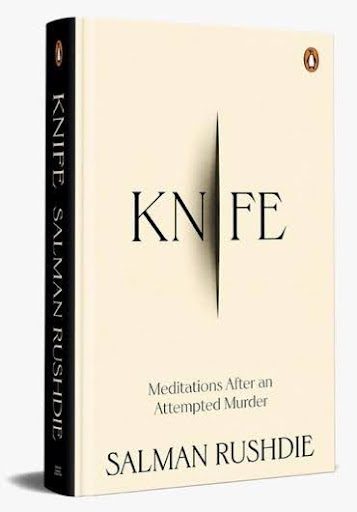

Published by Penguin Random House India

Imprint: India Hamish Hamilton

Length: 320 Pages

MRP: ₹699.00

At first, it reads like a diary, innocuously filled with medical procedures, family members’ travel plans, love, friendship, books and films, and thoughts on the nature of art and violence. But Knife is much more than that: this is Salman Rushdie speaking directly to the reader with his characteristic humor, an uncharacteristic tenderness, and absolutely no apology.

“I am content to be judged by the books I’ve written and the life I’ve lived. Let me say this right up front: I am proud of the work I’ve done, and that very much includes The Satanic Verses. If anyone’s looking for remorse, you can stop reading right here. My novels can take care of themselves.”

In contrast to the epic scale of his rich, layered storytelling, redolent with intertextuality, filled with characters bordering on the mythical, in language that itself is a living, breathing creature, this memoir is written with minimal literary embellishments. Here is a man gravely injured by a knife attack, yelping in pain, dealing with unpleasant and seemingly unending medical treatments, worrying about finances, concerned about his son’s fear of flying, all while deeply loving and being loved by his wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths:

“Let me offer this piece of advice to you, gentle reader: if you can avoid having your eyelid sewn shut…avoid it. It really, really hurts.”

“What makes hospitals happiest is when the patient says he is having bowel movements.”

“Striding forward, seriously distracted by the presence of the brilliant, beautiful woman I’d just met, and as a result not really looking where I was going, believing myself to be stepping through an open space, I hit the glass door hard, and fell dramatically to the floor. It was such a goofy, uncool thing to do.”

For decades we have come to associate Salman Rushdie with flamboyance, glamor, and gregariousness, and often forget that he is, after all, human: a writer of irreverent, brilliant, successful novels who creates magic realism on the page but does not believe in miracles in real life, who aches for the comfort of his own bed, his own home after weeks in the hospital. Knife is that rare memoir that brings to us the everydayness of his personality without letting us forget his genius as an artist. The attack left Rushdie blind in his right eye, with reduced function in his left hand, and partial paralysis of his lower lip. Blindness has been his deepest fear, and he is now forced to live with one eye, which is also under treatment for macular degeneration.

And then there are the bigger themes the book addresses: Should Rushdie have withdrawn the Satanic Verses which he calls “my poor maligned book” or apologised to those he had offended to a murderous rage, or led a low-key, low-visibility life? Many thought so. However, Rushdie did none of these; he wrote. And he lived. He fell in love multiple times and lived a life filled with friendship and public engagements. And finally made America his home.

Rushdie also shares his deep love and yearning for India. While sharing the statements of President Biden of the US, President Macron of France, even Boris Johnson of the UK condemning the attack on the 12th of August’22, Salman Rushdie shares, “India, the country of my birth and my deepest inspiration, on that day found no words. ” Later, he recounts his nightmares caused by PTSD, “I dreamed of returning to my beloved Bombay—not Mumbai—and kneeling to kiss the tarmac as I came down from the plane, but when I looked up there was a crowd shouting at me, “Dafa ho.” Begone.”

Satanic Verses is that rare book that managed to infuriate many Muslims, Hindus, and Western intellectuals at once. Banned in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Malayasia, and later in many other places, the novel unleashed a series of violent attacks across the globe: In 1991, Ettore Capriolo, who translated it into Italian, was attacked and stabbed at his residence in Milan. Shortly after, Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the book, was fatally stabbed near the university in Tokyo. In 1993, William Nygaard, the Norwegian publisher of Rushdie’s book, was shot near his residence in Oslo. Knife, clearly, has been a popular weapon with these assassins attempting to protect the world from books as dangerous as the Satanic Verses. Law enforcement officers in Chautauqua, New York also found numerous knives in the assassin’s confiscated bag.

Rushdie writes, “A gunshot is action at a distance, but a knife attack is a kind of intimacy, a knife’s a close-up weapon, and the crimes it commits are intimate encounters. Here I am, you bastard, the knife whispers to its victim.”

And later meditates, “When a knife makes the first cut in a wedding cake, it is a part of the ritual by which two people are joined together. A kitchen knife is an essential part of the creative act of cooking. A Swiss Army knife is a helper, able to perform many small but necessary tasks, such as opening a bottle of beer.”

And finally declares, “Language, too, was a knife. It could cut open the world and reveal its meaning, its inner workings, its secrets, its truths. It could cut through from one reality to another… Language was my knife. If I had unexpectedly been caught in an unwanted knife fight, maybe this was the knife I could use to fight back.”

In parts the book is sombre – many of Rushdie’s friends are dying or dead, and he himself goes through pangs of survivor’s guilt, in parts an affirmation of his conviction in the power of art, but above all, this is a love story between Salman and Eliza and to the fearlessness of a writer who in spite of the knife attack still chooses to declare, “I understood that my second-chance life could not content itself with private pleasures alone. Love, above all things, and work, of course, but there was a war to fight on many fronts—against the bigoted revisionism that sought to rewrite history, whether in New Delhi or in Florida”

This is a book we must all pick up and read – or listen to the audiobook in Salman Rushdie’s own voice – so that we don’t end up hating books without reading them or defining people solely based on press clippings. Above all, we must read this book to take a long, hard look at our own relationship with art, the idea of free speech, and violence in the name of religion.

By Kabir Deb

Interviews Editor

Kabir Deb: Hey Rochelle! How are you doing?

Let me kick this interview off by congratulating you on your new collection of poems Coins in Rivers. What made you write these poems?

Rochelle Potkar: So many reasons besides the compulsiveness to write.

To give shape to the chaos, restlessness, and turbulence that seeps into me from the world we live in today. Writing is catharizing. The need to empty oneself only to fill up again has always been the process.

In Four Degrees of Separation – my first book, I was raw while talking about the self, society, family, and relationships. In Paper Asylum my gaze was wider, sometimes cockeyed over the horizon. By the time I reached Coins in Rivers, I think I evolved much as a storyteller and screenwriter.

I believe through every piece of work, every art form, every story, every poem, we become a new person. But writing poetry for me still comes from impulsive and compulsive spaces. Unlike fiction or screenplays that are well-thought-out theses, outlines, and structures.

KD: In the poem The Girl from Lal Bazaar you shed light on the sufferings of women. Similarly in your short story The Arithmetic of Breasts grief becomes a physical entity. Tell us more about it.

RP: I have been curious about the human body, especially the female form that informs politics and society, sometimes as fodder, sometimes as prescriptive slates of do’s and don’ts. Food, clothing, strictures all oscillating around it. Human desire, the male and female gazes have intrigued me. We have always been torn between desire and violence. Shame, guilt, and fear realigning with lust and passionate yearning. And then the religiosities of dogma and decorum that shape our behaviours within confined and unconfined spaces.

In The Girl from Lal Bazaar I wanted to explore the grit and ambition that can spring up from anywhere. Even by the edge of the road. It’s always transformational and inspiring to witness the life of an invisiblized and marginalized woman subverting the trajectory of her destiny and dominant hierarchies. Even in our day-to-day unguarded life, we crave such rag-to-riches true tales.

Whereas my first short story The Arithmetic of Breasts’ in Bombay Hangovers, was

so many things:

But to this day, the ode continues, even outside the threshold of that story in society: ads on tightening, lifting, downsizing, resizing, and whatnots done to the décolletage. Sometimes we evolve oh-so-slowly as a species that some short stories never end.

I would like to bring attention two visual poems in this book:

In the first, I capture the risk versus opportunity conundrum. Here size is the double entendre. In the second visual poem, I talk of disparities between the genders. While the male species acquires transcendence (in mostly every career and life field) atop Maslow’s tilted pyramid, the women are mostly still grappling with primitive apes lower on the totem pole. Their climb through the pyramid is tougher. [Not to say the evolved Man is not dealing with primitive apes, but more the women have this ordeal. :)]

KD The collection moves from personal to universal. What was your objective in putting this collection together?

RP: My collage in Poetry is very disorganized, unlike my fiction, novels, and screenplays that are more planned and structured. Poetry gives me a lot of freedom to be wild.

In poetry, I write randomly and then piece together the mosaic into a semblance of section breaks. I believe in the Japanese poetic philosophy when they juxtapose images of a haiku, that no matter what you write, it will all come together as a mosaic of your life. Patchwork quilt-akin.

What I have noticed rather in my poetry books is a Pattern of Thought: all of my poems move concentrically expanding from the navel-gazing to the stargazing. From expanding personal orbits of query to social life, familial and, world affairs. Now it has even reached the galaxy and two or three stars.

KD: Quite a few poems here use fantastical elements. How do you balance between creativity, sensuality and reality?

RP: Humans need control. We brew fantasies so we can control what doesn’t exist. Want starts in a dream-state.

I don’t think sexuality, desire, and sensuality are far from how we experience the existential states of boredom, loneliness, sorrow, and grief. On a spectrum, all of this encompasses human living.

But sometimes we are caught more in one aspect of life than the other. For instance, if you are fighting a grave injustice or discrimination, you may not write a lot about sexual pleasure. That doesn’t mean you have not experienced it or desired it. But life and time is so limited, we pick our battles and stay the course. That’s why so many genres, tones, and themes exist. Pre-occupational hazards.

I think sensuous fantasies face a dichotomy in ever-changing societies. Then each word is a revolution, pushing the way forward, making space for what didn’t exist by materializing it on paper first, then in reality. Like a manifestation manifesto.

KD: What role does gender play in relationships and how do we change it?

RP: A lot of life is non-gendered, according to me, in the way it renders itself. For e.g. grief, happiness, lust, and desire hit both men and women in the same intensity. But the divisions of time into existential chores and gender roles allow each to experience these differently. Now with the laundry and cooking modernized, ridding women of chores, it has somewhat equalized the experience.

Men tend to externalize their emotions and women internalize more, I have heard. But even if that is true, it’s person-to-person specific.

Where gendered violence or gendered discrimination is concerned, this doesn’t hold true.

In one of your poems, you write that the destiny of nature (rivers) runs through those who live by embracing its greenery and fertility. How do we as writers and poets feel responsibility towards environment and its rampant degradation as the capitalist world teeters heavily on consumerism.

By not being climate deniers? But adapters. I think earth-awareness is important whether via the school syllabus or a self-learning one. And then making choices accordingly.

Even capitalism will need to think of the Environment, if it has to sustain itself over the bottom-line-P&L-ROI-driven long run.

I think consumption and consumerism have more to do with mind-set. When does one feel content? When does one stop wanting things? This has a philosophical connection to the self-knowledge of death. Every day we are dying a bit or going toward death, so in that sense should we be living it up by consuming more, or begin the slow process of pruning? Should we be sharing our resources more freely because we are all walking the same road, same journey? It’s a matter of individual choice.

Bare Bones is an independent publishing house based in Gurugram, India. It was founded in March 2023 by Sahana Ahmed and Captain Shakil Ahmed.

Sahana is a poet and novelist. She is the author of Combat Skirts (2018) and the curator and editor of Amity: peace poems (2022). She was awarded the ‘Woman of the Decade’ title by Women Economic Forum in 2022.

Captain Shakil is a distinguished military veteran and a recipient of the coveted ‘Sword of Honour’ from Officers Training Academy, Chennai. He served with distinction in the Corps of Army Air Defence, contributing to significant operations, and is currently employed with a tech unicorn as a Senior Vice President.

Bare Bones aims to educate and entertain children and young adults through picture books, early readers, chapter books, and more. General-interest books for ages 18 and over will be produced under the imprint Bare Bones Plus.

VTRN is an imprint for inspirational military literature, published in association with VTRN Global Foundation.

The Bare Bones vision statement is simple: Empower future citizens through well-crafted books. They have award-winning authors and artists on board, including Vinita Agrawal, Maryam Ahmad, and Riya Singh.

The first Bare Bones title is scheduled to be released in June 2024. For more information, please visit their website at https://barebonespublishing.in.

Bare Bones is on X and Instagram: @barebonesllp

Join our newsletter to receive updates