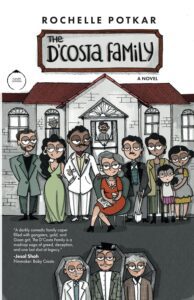

By Rochelle Potkar

The 1990s

The shrill twittering of birds in the Burgundy House backyard stopped Rita D’Costa from eavesdropping on what her eldest son Pedro was saying to visitors in his den. This morning it was the hurly burly Sashi Vaswani – the most important element in their lives – saviour, kingmaker, and key-maker to all their locks and deadlocks.

What she could hear were snippets of laughter and whiffs of phrases that made no sense. Even after she shushed the maids in the kitchen, saying, ‘Use the stone grinder. The masala mixer is too noisy,’ she couldn’t hear a word.

So, she had marched into the backyard, with her jaw firm over her obstinacy to study the birds swelling in their nests on the mango tree. Their ruckus amplified into the town’s silence.

At 5 feet 2″ and at 67, Mrs. Rita D’Costa stood backstraight over the length of her spine. No misery or tiredness of any day could ever let her stoop. That was her preserve of pride and self-respect — the only thing gifted from her family, The Joseph family. Never mind that her lacy camisole hem showed longer than her floral dress. There was a time her grandmoth would scold her for that. Now she was a grandmother herself her talcumed face gleaming with wrinkles around her green eyes, framed by her silver hair that was bob-pinned into a puff. She dabbed her sweating forehead with a handkerchief pulled from the front of her dress.

Around, the dusty town of Callian – a satellite town to Bombay, rolled into a new day as if it were yesterday. Even if this town picked up speed in hiccups, it appeared on standstill. Like another Malgudi, thought Rita, squinting at the canopy of the mango tree.

Babu, the Callian Municipal Corporation (CMC) tree-cutter had arrived and stood beside her. She nodded at him. Puny, cock-eyed, and knock-kneed he was agile at climbing the tree – almost apelike. Rita found it difficult to trace him over the bark and branches. She followed the bare of his back that clung to his sweaty, loose vest.

The tree-cutter enjoyed the view of the esteemed Burgundy Estate. No tree-cutter in CMC had the noble fortune of viewing this huge plot from the inside — its empty grounds flanked by 20 cottages for tenants, and on the other side, the landlord’s mustard, red-roofed bungalow with porches, ornamental columns, pilasters, and embellished veranda railings. A balcaõ with built-in seating on a high plinth flowed out to a maroon staircase, that faced the main road. The calligraphic lettering under the roof read: Burgundy House | 1935 standing proud, as if looking down at the tenant settlement through its dome-arched windows with mother-of-pearl panes.

Rita, in her red-checked apron, yelled at Babu, pointing to the twittering knot at the left side of the tree. She inserted her little fingers into her ears and rang them as the birdsong grew shrill.

Babu held his long garden scissors, as a wooden axe dangled from his waist. He couldn’t help laughing, flashing his tobacco-gutted teeth. “What’s wrong bai? They’re just singing their song!”

“Singing!? If they were in chorus in a choir that would be good. But look! All at different times. I am going deaf!”

“Not only sparrows. Mynahs, parrots, rollers, robins, koels, pittas, bulbuls…”

“Yeah, so you can’t cut the birds, no? You have to cut the branches and the leaves… so do it now! Get on the job!”

“But this is natural music, bai. Unlike road traffic or loudspeakers or what plays during our weddings and festivals…”

“Cut! Cut! Cut! I want to hear no more of your pah, pah pah even,” Rita closed her ears with her palms.

Babu hacked away a branch but another one loosened, breaking his balance. He fell close to where Rita stood. They shrieked and yelped out of each other’s ways in that leafy mess. She was a ball of leaves and mud, and the tree cutter had the privilege of holding her hand and putting all his force and breath into yanking her up to her feet, while ignoring her wrinkled, spider-veined thighs. It was a tale he could tell his grandchildren. That he had touched Rita D’Costa. But this was enough to hunt the twittering ruckus away. A cloud of birds flew and smattered over Callian’s skies and over its horizons returning to them a deafening swatch of peace.

It wasn’t that Mrs. Rita D’Costa was heartless. At one point, she had loved lawns and gardens, enjoying the fluff and fur of rabbits and puppies and admiring the flutter of yellow butterflies. But that was when she was in her father Anton Joseph’s home. Now, and for many years before this, things had been difficult. Hard and cold as metal, where all soft things had gone elsewhere to roost.

Rita walked through the rooms of Burgundy House. Not on any given day could she forget that the furniture in the D’Costa’s house had come from her own – the Josephs’ home. The Burma teak carved almirah, the grand piano, the rosewood swing, and the home shrine that roofed Joseph, Mary, and Infant Jesus. The D’Costas had picked these from there on the Day of Bloodshed. These that were now loving pieces of her wounded heart, polished with Brasso – handles and knobs, and varnished in strong-scented polish. These, standing like racketed and harvested organs implanted into this godforsaken abode. She stood in front of the shrine and crossed her heart, murmuring a prayer, as the smell of death lingered, as if the Angel of Death had decided to stay on. That’s why she could never sleep on any night. Not a wink from the time she first came to this house many years ago as a bride.

Now, she proceeded to do what she hated most.

Don Pedro, her eldest son, all of 39, was pacing in the foyer, chewing on his lower lip – something he did when no one was looking. His bodyguards – Barrett, Jarrett, Brandon, and Landon -two sets of twins stood pinned to the wall with empty AK-47’s, like wax statues. They could even inhale and exhale in unison.

“Mummy, what happened? Is everything alright?” asked Pedro.

Every time he called her Mummy, the hair on her nape stood on end. “Yes, your Papa’s fine. But I just wanted to ask…,” said Rita.

He knew it already. “Not again, Mummy. You know this will distract you. Everything is bought for, isn’t it? What’s less is in the house? What do you need money for?”

“Even children have pocket money!” snapped Rita. “You won’t even let me buy the greens and groceries without your stamp!”

“Oh, come on! If you are careless, you know the maids might steal it, or you might forget where you kept it. Why bother? Ask me what you want, and I will get it for you.”

“Seneca’s marriage is up. We need to buy dresses… materials…,” said Rita, biting her lip to stop it from quivering.

“I will send the money directly to the shops, don’t you worry.”

“The marriage will cost so much. Arrangements! Everyone wants cash.”

“Then send them to me. With bills and receipts. I am there to handle it.”

Rita’s face reddened as her voice turned crotchety. “You think I can’t manage money. In my father’s house, in my days, I would be given so much, just lying here and there. I couldn’t even count all the notes…”

“Mummy, mummy, why dig up the past? This is not your father’s or grandfather’s house. Or those days. Those days are gone!”

Rita realized the impossibility of this talk again.

The only way out of such misery: her kind of poverty, with not even 10 rupees in her pocket, would be to sit on that throne in the den. But when? And how much longer? This had been her question for years. And how? How soon? She had got Theodore to change his will, but even that didn’t add much. Plans worked like tyres not when they were rounded and filled with air, but when they hit the road and rolled on gritty gravel. The proof of the pudding was in the Yorkshire pudding, her father always said. And here there was no pudding, not even the recipes. “Okay, then at least tell me about the flats in the new tower. How many for each person?”

“One is all that I can promise. One 3 BHK for each family member,” said Pedro, his eyebrows widening into a smile. No human looked as ugly as him then with his balding head, pot belly, and flabby nose.

“That’s all? We should at least get a penthouse or a… what you call them… a sky villa and an extra flat on the lower floors for parties, functions, and get-togethers. Can I see the blueprints?” said Rita.

“They… are not yet done, mother of mine. But what would you do with so much? I was thinking a 1 BHK would suit you better or you could just live with me and Annette in our penthouse. Or with Jason and Blanca. All you need is one small room – and of course your Library. It will tire you walking in large areas. Then you will get sick, and need a hospital bed…”

“When can I see the house papers, the maps, the drawings?” said Rita, stamping her feet to the ground.

“Alright, soon!” said Pedro, enjoying her irritation.

Had her father Anton Joseph been around, he would be saddened to know how his businesses had been renamed by the D’Costas. The spurious liquor bottles, the names on the fleet of trucks, the front shops, even the casino.

Rita marched back into her kitchen of many years. Even though the stone grinding would take longer and ache their hands, the maids Myna and Philomena followed her orders and crushed Kashmiri chillis, cloves, cardamon sticks, jeerey-meerey, ginger, garlic, tamarind, and fenugreek. They took turns grating hills of coconut pulp, sitting on a wooden grater with a curved blunt blade for the noon curry.

In all these 30 married years in the D’Costa house, Rita still hadn’t gotten used to making Goan food. Her kitchen should have had only Anglo-Indian dishes. Where were her mother’s dishes of meat brown stew (pish-pash), minced meat fricadelles, steak smores, railway lamb curry, onion soups, crumb chicken, and Yorkshire pudding? She looked at the pots and pans with estrangement. All these years she had bent her head low and cooked Goan food: vindaloos, xacutis, fish, and prawn balchaos, but never once Anglo-Indian dishes. No one knew what this meant to her. This gross humiliation, this deprivation. She was being looked through, made invisible, small. Turned into powder masala. A near-zero. Even if she didn’t have a mother-in-law to hover over her, it was Theodore who passed instructions in the kitchen of what could be cooked and what couldn’t.

To the world outside, the Hindu world, Muslim world, the Parsi world, and Sikh world, an Anglo-Indian was hardly different from a Goan. They had the same Christian sounding names. If they had accents, they could pass for Europeans, Americans, and British. But Rita knew deep inside how different she was from a Goan. They were a culture, a community. They had a history from the times of the British and the East India Company.

But never mind all the contributions the Anglo-Indian community had made to India, post its independence in four Mahavir Chakras, twenty-five Vir Chakras, two Kirti Chakras, two Shaurya Chakras, there were always some in every clan bound to turn their wool a shade darker. Blacksheep, they were commonly called.

Rita’s father, Anton Joseph was the son of a British officer – Sir Wolverine Joseph – a high-ranking Railway Official, whose internal injuries from an unnamed battle had begun to collapse his blood vessels. He preferred to die in the tropic climes of new, independent India than in the cold of England. And so, his son Anton too sprang roots into Indian soil. Anton’s mother was Bengali, and his father had taken an instant liking to her when they first met at breakfast at the Calcutta Rangers Club. She had newly returned from London, and was never tired of mouthing poems by Toru Dutt, Emily Pauline Johnson, or Henry Louis Vivian Derozio to summarize an unremarkable moment. Aaratrika was her name. Later shortened to Aara, after marriage. At their first meeting instead of replying with a hearty Good Morning to Wolverine, Aaratrika recited Emily Pauline Johnson’s poem.

‘An’ then-a voice, an Indyan voice, that called out clear and clean,

‘Take Indyan’s horse, I run like deer, wolf can’t catch Wolverine.’

I say,‘ThankHeaven.’TherestoodthechiefI’dnicknamed Wolverine.’

Wolverine had never felt this indulged and graced before. Aaratrika’s whisperings in English with a Bangla heavy accent sounded so musical that he wanted to listen to her for the rest of his life. He sought a repartee from Henry Louis Vivian Derozio’s verses after reading them several times:

With surmah tinge the black eye’s fringe,

‘Twill sparkle like a star;

With roses dress each raven tress,

My only loved Dildar!

In Busrah there is many a rose

Which many a maid may seek,

But who shall find a flower which blows

Like that upon thy cheek?

But after Anton Joseph’s parents died—his mother from Cholera—life became a fugitive one for him over an accidental crime. He had borrowed money from a friend on the sly to start a decent business that his father would have never approved of, instead of a well-paying Indian Government job. He gambled the money to double it, lured by the attendant at the gambling den. But instead of winning, he lost all but 10 rupees at roulette and baccarat, and in a sudden fit of rage stabbed the attendant. The attendant succumbed to his open wound – a gash at the side of his stomach and Anton had to run as far as he could from this epicentre of bad luck.

He escaped to the Port of Bombay. When the police searched for him there, he boarded the first outstation train that sped along into the distant flat horizons and countryside to stop at the last terminus: Thane. From there he took a long journey, overnighter bus to as far as it would ply: Callian. And that’s how Anton Joseph found his promised land. His little Goa or Sikkim. The reigns never slipped again from his hands, as he saw the good barren canvas of an empty town on which to build a civilization.

But if time can slip by, so can history and legacy.

And that’s why today with a feeling of uncontrol, Rita decided to take at least some matters into her hands with the hacking of the twittering on the tree. She continued now with her wretched life of humidity, waiting and praying in her scullery of cutlets and curries.

But the next week brought her a change in fortunes.

She was called from this very same kitchen by maid Myna to urgently go into her bedroom.

Her husband, Theodore D’Costa, all of 76, lay on the oldest four-poster bed, suffering from cirrhosis. Rita sat at the edge of the bed as he slithered his wrinkled hand into hers. She whispered prayers and novenas as he was laboriously breathing his last.

If Theodore was a dark-skinned Goan, Rita was shades fairer, that by now watching each other’s faces reassembling each other, they had just become photo-negatives of each other. Swollen cheeks on a puckered face, a beatific smile and kind-hard eyes, Rita, short at 5.2”, Theodore, tall at 6.1”. Watching him, she inhaled deeply and waded through the smells of incense sticks, candle wax, and pyrethrum paste coils from under the bed to ward off mosquitoes and evil eye. To add to it, the strong smell of burning camphor in a prayer chalice brought from the church, kept in the corner of the room. The Angel of Death was somewhere near.

Rita slyly watched the grandfather’s clock. It was not to note the exact time Theodore might expel his last breath, but rather to appraise herself of how delayed the lawyer Kaitan Lopez was in bringing Theodore’s will to them. This business of death was taking too long.

Usually, deaths by road accidents and freak bullet injuries were faster. Laborious deaths were not something she could wrap her head around. She looked at the slowcreaking fan and pulled out her lacy kerchief to dab off her sweating face. Her excess talcum gathered in white rings around her cheeks and neck now. Outside the window, the baby-blue summer skies had broken into a monsoonal grey. The first showers with thunder and hazy drizzles were in. What a respite it was for the severity of sweat drying over her back and nape. She drew in a breath of fresh moistness from the mud.

“Biscuits… biscuits…,”said Theodore, a death rattle labouring out of his chest. He smiled at the beatific face of his wife. “You know when I first fell in love with you? In Rome, after the Vatican City. When we were separated. That stupid coach took you away…”

“Oh yes, that train that went the other way,” said Rita, grinning at Theodore, “Oh, what a trouble that was, dear me. What chaos!”

“I stayed alone for three days,” he gulped, “waiting for you to be brought back by the police.I realized then …. how much I loved you. Each day – a punishment of not seeing you.”

Rita’s eyes shone. “Yes, Theo, I missed you too on those three days. That every time…”

“Every time?”

“Every time a man came to help me – a waiter, bus conductor, or policeman, I rushed into their arms to cling and hug them. I even kissed them in memory of you. But… that Italian doorkeeper was the best I could have!!! He gave me company for one whole warm night. The way he hugged and cuddled me and never left me.”

“What! You betrayed me? You…?”

“Hardly, Theo.I thought of you only as Iloved him… Only your face came to my mind. Your eyes … as I screamed and yelled in excitement. Oh, he was good. The best I have ever had!”

Theodore’s chest heavedwith an attack of sudden realization that his wife had never really loved him.

This was not the feeling one should have had to die with. But in death, there are no choices of what reasons might emerge as the final bidding of goodbyes.

Theodore D’Costa died with no peace.

But then peace wasn’t on top priority in the D’Costa Family.

It never had been.

And not from when the Joseph Family had been in town.

Excerpted with permission from The D’Costa Family by Rochelle Potkar published by Clever Cocoon Publishers 2025

Rochelle Potkar is an alumna of Iowa’s International Writing Program (2015) and a Charles Wallace Writer’s fellow, University of Stirling (2017). She is the author of Four Degrees of Separation (poetry) and Paper Asylum (haibun) – shortlisted for the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize 2020, Bombay Hangovers (short fiction), and her latest poetry collection Coins in Rivers. Her poetry film Skirt showcased on Shonda Rhimes’ Shondaland. Her poems To Daraza won the 2018 Norton Girault Literary Prize UK, and The girl from Lal Bazaar was shortlisted at the Gregory O’ Donoghue International Poetry Prize, 2018. Widely-anthologized, she has read her poetry in India, Bali, Iowa, Macao, Stirling, Glasgow, Hongkong, Ukraine, Hungary, Bangladesh, Dubai, and the Gold Coast, Australia. Her writings have been translated into Arabic, Hungarian, French, Spanish, Hindi, Marathi, and German. She also co-authored The Coordinates of Us/ सर्व अंशांतून आपण – a bilingual cross-translation of English/Marathi poetry. As a poetry book critic, her reviews have appeared in Wasafiri, Sahitya Akademi’s Indian Literature, Asian Cha, and Chandrabhaga. Her first screenplay ‘A Brown coat’ was a quarter-finalist at the Atlanta Film Festival Screenwriting Competition 2020. She is an industry expert on syllabi boards (English Lit.) of two top Mumbai universities. She was invited for four consecutive years as a creative-writing mentor to Iowa’s prestigious International Writing Programs, Summer Institute 2019 and Between the Lines 2022, 2023, 2024. She conducts regular online poetry workshops at the Himalayan Writing Retreat. https://rochellepotkar.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates