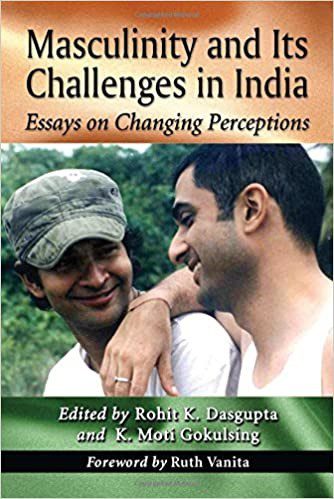

While essays in the book meticulously engage with changing perceptions and ideas of masculinity, touching upon diverse texts such as VS Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas, Ritwik Ghatak’s Partition Trilogy, and even the (post)-colonial subject in Amar Chitra Katha comic books, curiously, there is no essay which discusses the film whose still image adorns the cover, perhaps functioning as a succinct ensemble of ‘changing perceptions of masculinity’ underway in Indian society. My sister and I had watched My Brother Nikhil together in 2006. More than anything else, we were deeply moved by the infinitely affectionate, empathetic relationship between Nikhil (Sanjay Suri) and his sister, Anamika (Juhi Chawla).

However, it was much later, when I began my doctoral studies in Masculinity Studies, that I revisited the film, and its other dimensions, politics, and concerns became conspicuous – the heartfelt depiction of Nikhil and Nigel (Purab Kohli)’s relationship (which was light- years away from Bollywood’s otherwise stereotypically caricaturised portrayal of same-sex relationships, especially between gay men), Nikhil’s HIV+ condition, and later suffering from AIDS, not only in terms of health, but also in terms of the societal and legal stigma attached to it. Nikhil’s character was based on Dominic D’Souza, an AIDS-activist based in Goa in the late 1980s. While contextualising the politics and position of My Brother… in Indian cinematographic history may lie beyond the scope of this review, what stands to attention is that the film, sandwiched as it was amidst other similar big banner ventures/films of that time which attempted to interrogate, or at least imagine alternative representations of masculinity {such as Dil Chahata Hai (2001), Devdas (2002), Koi Mil Gaya (2003), Omkara (2006), and Rang De Basanti (2006)}, managed to successfully articulate its own aesthetic and critical vocabulary to represent a version of (marginalised) masculinity, with grace and compassion not seen in other films of that day, that too (as Onir informs us), within strict monetary limitations i.e. they completed shooting My Brother… in 27 days, given the budgetary constraints.

When Candidness equals Candour

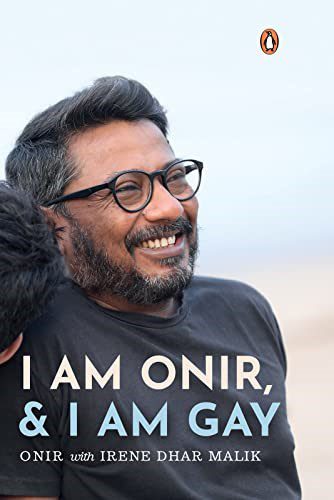

I am Onir and I am Gay, Onir’s delicately penned memoir sheds light on the background to, and making of My Brother…, among other vignettes from his life.

There is something utterly candid, warm, and vulnerable about Onir’s recollections of his childhood days, his film-making journey, and his various friendships and relationships. Perhaps my reading was coloured by the impact that My Brother Nikhil had had on me, and hence, the voice, tone and tenor of the memoir, seemed imbued by the warm, sympathetic, intelligent narrative voice of Onir’s film. One feels as though one is sitting with Onir, on a warm, sunny day, over coffee and bagels, while he recollects what made him who he is today. For instance, read his recollections of the time he was involved in the making of Daman, with Raveena Tandon and Sanjay Suri,

“Coming back to Daman, Sanjay, Ravs and I bonded famously during the shoot. Some nights, Ravs would take us out for a drive, during which she would suddenly switch off the headlights for a few seconds and we would be driving in pitch darkness. Those few seconds would seem endless, out of this world”.(p.135)

Vividly Sketched Childhood Vignettes

In a lot of places, especially in the initial portions of the memoir, Onir’s recollections reminds one of the nameless narrator in Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines (1989), and the latter’s experiences, growing up in the Calcutta (now Kolkata) of the 1980s. For instance, the following passage from I am Onir… where he reminisces huddling with his grandfather and listening to stories of the freedom-struggle and Partition,

“Winter evenings with Dadabhai meant us sitting in the verandah, huddled in the warmth of his all-encompassing shawl. It must have been really big because all three of us would be wrapped in its folds along with him while he told us the most amazing stories. They were mostly ghost stories, but there were also some stories about how he and Didabhai had trained in stick fighting (lathikhela), a traditional Bengali martial art form, so as to fight against the British, stories about the freedom fighter Master-da (Surya Sen), and of Partition”. (p.13) would remind readers of the nameless narrator in Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines, listening to his grandmother recollect a similar episode from her college days in Dhaka,

“My grandmother’s mouth tightened into a thin line…And then, her voice slow and dreamy with the effort of recollection, she told us about a boy who had been in college with her in Dhaka, decades ago, in the early twenties. He was a shy, quiet boy with a wispy little beard, who lived in the lane next to their in Dhaka’s Potua-tuli. He always sat as far as back as possible in the lecture room, and sinc he never said anything nobody took much notice of him…then one morning, when they were half-way through a lecture, a party of policemen arrived, led by an English officer, and surrounded the lecture room”. (p.28)

Likewise, Onir also recollects particular instances which resonate with, and shine a light on what it means to grow up queer in the Indian context. The following anecdote from the chapter, ‘The Dancing Boy’, is telling in this regard,

“Very often, on the first night of our stay at Dadabhai’s home, there would be a performance by us kids. I remember I used to look forward to the evening when my maternal aunts (Mitamashi and Khukumashi) would dress me up in a ghagra and apply make-up to my face. I would wear a veil and dance to Hindi film songs with total abandon. Sometimes I would dance like Helen, sometimes Bindu . . . and no, I didn’t identify myself as a girl; I think I just wasn’t conscious of gender boundaries. Until one evening when I was a student of class eight and must have been around twelve years old. Ma and Baba had a talk with me after the performance, telling me that I was too old to be dancing like a girl and that it was very embarrassing for them to watch me dance in such a shameless way. It was one of those rare occasions that Ma and Baba disapproved so strongly of something I did. That night, my dreams of being a dancer were shattered, and I wept a lot.” (p.23)

‘Gay & More’ & Other Masculinities

Onir’s authentic voice, and the candidness with which he recollects, analyses and comments on his experiences ensures that the book resists being reduced to ‘Inspiration Porn’, or lapsing into the ‘underdog/ victim’ narrative –something that narratives from marginalised positions risk becoming vulnerable to.

While Onir is gay, and the title of his memoir makes an emphatic announcement of his sexual orientation, the memoir, in its entirety, sketches a fully-lived life-narrative, in which sexual orientation is only a part of his overall identity. As he confesses,

“Maybe that was also the way I wanted to be seen—to be loved, respected and heard as a human being who is perhaps interesting. My sexuality is a part of my identity, a very important one, but not the all defining factor. I am gay. And more.”(p.138)

Further down the book, one realises that only someone with the sensibilities and sensitivities shared amongst Onir and his peers such as Sanjay Suri, Ambika (Sanjay’s wife),and Irene (Onir’s sister), could have made socially-aware, morally-rooted films, such as My Brother…, I Am (2010), and Chauranga (2016). For instance, reminiscing about the background process behind the making of My Brother…, Onir writes of Sanjay,

“His eyes were constantly moist as he spoke about the character and he said, ‘Let’s make this film.’ He was not worried at all about playing a gay character and thought that the role was a challenge he would cherish as an actor. I don’t remember ever sitting with Sanjay and discussing the ‘gayness’ of the character. For me, that was in his gaze on Nigel. I have never believed in or agreed with the way gay characters were perceived and portrayed in most mainstream Hindi films. For me, Nikhil was gay and more. And with Nigel, I wanted an element of the ‘feminine’ ”. (149) (Emphasis mine)

Perhaps, it takes someone like Sanjay Suri (as opposed to muscular, hyper-masculine, ‘action-heroes’ of the day), utterly secure in his masculinity as well as his professional prowess as an actor, to agree to play a ‘gay character’, in an industry which is quick to typecast actors into specific moulds. As mentioned, this thought-process, of being ‘gay and more’, not only runs through the film, but also through Onir’s memoir.

Another aspect which sheds light on alternative models of masculinity are Onir’s descriptions of his father, as well as other men, such as his friend Sanjay, and colleague, PurabKohli. To illustrate, of his father, Onir writes, “He had very few close friends, and family mattered to him the most. What was amazing about him was that he shared all the housework with Ma—cooking, raising us, washing clothes, shopping, teaching us. In everything, he was an equal partner. (p.21)

In Closing

Onir’s memoir is a refreshing, by turns introspective and funny, and wholly honest telling of a life-story which refuses to be straight-jacketed in singular identity-markers. It brings to life the challenges and difficulties which came his way, not all of which he triumphed, while simultaneously acknowledging the safety-net of friends, family and peers, which helped him sail through and be what he is today. In closing, the following anecdote serves as a porthole into the book, and its utterly engaging style of narration,

“Urmila Matondkar, who was a partof the cast along with Jimmy Sheirgill, Sanjay and Juhi, wasn’t verycomfortable with on-screen kissing. It wasn’t that commonplacein mainstream Hindi cinema back then, and I didn’t really try hardto convince her as I (rather stupidly) had felt too embarrassed todo that. Since then, her name is saved on my phone as ‘Kiss menot’. Jimmy was someone I already knew and he was also friendswith Sanjay. We became very good friends during the shoot.Generous, kind and always smiling, Jimmy was a party man whowould constantly take me out to party. Just before the shoot, hetold me that he had been thinking about his character, and hethought that the character should have a tattoo saying‘sex maniac’as that was the essence of Sameer’s character. That suggestion didnot work for me, but he became ‘sex maniac’ on my phone! Manyyears later, I was bathing when my housekeeper screamed fromoutside the bathroom door that ‘sex maniac’ was calling!”

Ankush Banerjee is the Books Editor at Usawa, and the author of An Essence of Eternity (Sahitya Akademi, 2016). He loves Biriyani, visiting old bookshops, and the sea. His work has appeared in The Tupelo Review, Eclectica, TBLM, Indian Express, The Hindu, and Jaggery among others. His second book of poems is forthcoming soon.