Burnt Imaginations: ‘The Body’ in Andrew Davidson’s The Gargoyle: Adyasha Mahapatra reviews Andrew Davidson’s novel

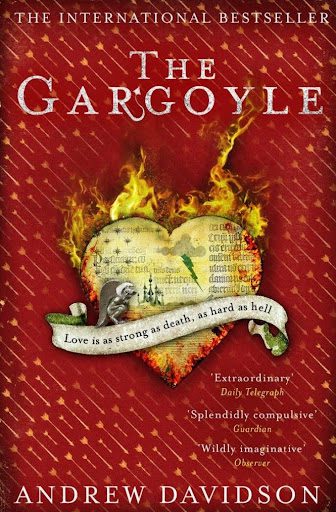

Title : The Gargoyle

Author : Andrew Davidson

Genre : Fiction

Language : English

Publisher : Canongate Books

Year : 2009

Pages : 499

Price : Rs. 1282/-

ISBN No. : 978-0307388674

The way we have come to look at our corporeal self (or not look at it for that matter) says much about us as a race. A lot of effort has gone into defining the physical body through art and thinking about it in terms of its metaphorical value, all in an attempt to distract ourselves from the simple fact that the physical body is crude and fragile in essence. We are repulsed by blood and gore not because it is unfamiliar but because we recognize it as too close to reality. A transparent understanding of the body therefore lies in the very aspects of it that elude acknowledgement and discussion. Few readers would consider Andrew Davidson’s The Gargoyle as a novel about the body owing to the presence of more pressing themes within its narrative. However, there aren’t many works that have taken such an attentive approach towards depicting the body and its many facets as The Gargoyle. By not making it the dominant theme of the story, Davidson has invited the readers to observe it obliquely between their inhales and exhales, thus permitting an organic awareness of its dynamics.

Since its publication in 2008, Davidson’s debut novel has attracted mixed reviews from his readership. The novel defies identification with any particular genre but the general consensus has viewed it as a dark romance with elements of historical fiction and the macabre.

Through his unnamed protagonist, Davidson explores the chain reaction that is triggered when the thin layer of skin separating us from our sensitive entrails is eliminated. The narrator meets with a near fatal accident in the first few pages of the book and wakes up in a Burn Ward with third degree injuries all over the critical parts of his body.

In the subsequent chapters, the readers discover the narrator’s cynical and sardonic demeanor and the traumatic past responsible for it. It is revealed that he used to be a porn star, making the accident a turning point in his life. We realize that he has not only lost parts of his body but also his bread. A once attractive man, the narrator is now a grotesque being (not unlike a gargoyle) patched up with numerous skin grafts and atrophying muscles. The first quarter of the book is spent with the narrator bedridden in the Burn Ward, waiting for excruciatingly painful procedures to break him even as they make him up. Bitter and weary, he offers us detailed descriptions of the procedures he undergoes, including textbook accounts of the human body and what happens to it when it gets severely burnt. Davidson is crafty in that he takes his readers on a journey of pain and empathy by focusing on the physically damaged body under the pretext of medical facts and letting it inform the psychological pain that must automatically accompany it. His writing is visceral which makes the narrator’s torturous reality more tangible for the readers. As he alternates between masochism and resignation, the narrator doesn’t shy away from making his readers a part of his pain. Consider the following passage,

“I peeked under my body bandages, curious to see what was left of me. The birth scar that had spent its entire life above my heart was no longer lonely…Each day a procession of nurses, doctors, and therapists waltzed into my room to ply me with their ointments and salves, massaging the Pompeian red landslide of my skin.” (28)

The empty hours he spends lying still also afford him a peek into the way people respond to bodies that have deviated from the normal:

“Unable to tend yourself in a hospital, strangers plague you: strangers who skin you alive; strangers who cannot possibly slather you in enough Eucerin to keep your itching in check; strangers who insist on calling you honey or darlin’ when the last thing in the world that you are is a honey or a darlin’; strangers who presume that plastering a smile like drywall across their obnoxious faces will bring you cheer; strangers who talk to you as if your brain were more fried than your body; strangers who are trying to feel good about themselves by “doing something for the less fortunate”; strangers who weep simply because they have eyes that see; and strangers who want to weep but can’t, and thus become more afraid of themselves than of burnt you.” (44)

The only breath of fresh air the narrator finds in his purgatory is Marianne Engel who happens to be a fellow patient from the psychiatric ward and insists on knowing him and all about his life from 700 years ago. Though the narrator’s logical mind assumes her to be schizophrenic, her tales of love about people she has known over the centuries and her uncanny knowledge about his present life offers him a window of escape from his painful reality and more surprisingly, makes him want to believe in love once again. The most striking thing about Marianne is her physical appearance. The narrator being an astute observer lets his poetic self take over as he compares her hair to “Tartarean vines that grow in the night, reaching up from a place so dark that the sun is only a rumor.” (p.53)

Aware of the contrast he must pose to her beauty, he observes, “her eyes, also, are going to force me to embarrass myself. They burned like the green hearts of jealous lovers who accuse each other at midnight. No, I’m wrong, they were not green: they were blue. Ocean waves tossed around her irises, like an unexpected storm ready to steal a sailor from his wife.” (p.53)

The change in the narrator’s language while describing Marianne betrays the medieval temperament he still carries in himself, just like his birth scar.

Marianne Engel however, is no stranger to the hideous and the grotesque. She reveals that she sculpts gargoyles for a living. Her technique involves communing with the gargoyles already present in the blocks of stone and carving them out of it to set them free. Her dedication towards carving these monstrous beings helps the narrator accept his own reality. The tales of love that Marianne narrates are tragic yet triumphant. Davidson’s depiction of the medieval ages is thorough and addresses one of its distinct features – heartbreak and woe ending in physical tragedies because it was common and rather easy to get physically harmed in those times. The body was more expendable; people lived a physical life and the punishments for crimes and moral digressions were also corporeal. What he observes about war and history in the middle ages still holds true, “as soon as a man has chosen a side in war, he’s already picked the wrong one” (p.237) for “all history is just one man trying to take something away from another man, and usually it doesn’t really belong to either of them.” (p.237)

The physical body has always had a significant role to play in tales of romance, conflated as it is with desire and sexual union.

Davidson has not dwelled on this hackneyed trope and still managed to incorporate the body as one of the significant aspects of the story. It helps raise a relevant question about our selective interest in our physicality: Is the body relevant only if it acts as a vehicle for love and lust? Can we still be mindful of it without placing it in context of another body? The many stories in Davidson’s novel, especially that of Marianne Engel and the narrator himself provide a few interesting perspectives, through an atmospheric and captivating journey. The physical body also serves as the only anchor for the readers as they take multiple leaps across places and time.

The Gargoyle was an accidental, albeit happy and opportune discovery for me as it helped me navigate my own purgatory last year. Despite the divided opinions, I was able to savour all its twists and complications because I went into it without any set expectations or touchstones in mind. It is as the narrator says, “accidents ambush the unsuspecting, often violently, just like love.”

■■

Author’s Bio:

Adyasha Mohapatra is a Research Scholar in the Department of English, University of Delhi. Prior to pursuing her research, she worked as Guest Lecturer in the Department of English, Utkal University for three years. She is passionate about poetry, visual arts and cinema which also constitute her academic interests. She likes to live off the social media grid and relies on a daily dose of tea to quell the anxieties of urban life.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates