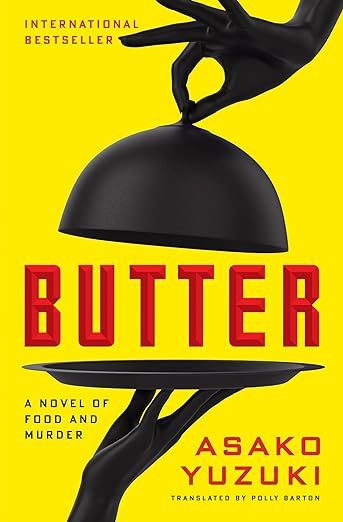

Title: Butter

Author: Asako Yuzuki

Genre: Fiction/Novel

Language: English (Translated from Japanese by Polly Barton)

Year: 2024 (English publication; originally published in Japanese)

Publisher: Pan Macmillan

Pages: 465

Price: INR 475.00

ISBN: 978-1035009589

Butter is the first of the books by prolific Japanese writer Asako Yuzuki, to be translated into English. Translated by Polly Barton, it combines mouth-watering descriptions of food with intrigue, character study, and social commentary.

Butter follows Rika Machida, a journalist profiling the infamous Manako Kajii, a gourmand and a suspected serial killer. Kajii has been accused of murdering three of her lovers, all of whom she seduced through her delicious home-cooking. A woman of expensive tastes, who enjoys luxury, particularly when it comes to food, Manako Kajii is also an avowed anti-feminist. She is clear from the start about her distaste for feminism, and for working women, believing that it is women’s nature to serve men. This naturally startles Rika, a woman who has spent much of her life earning a place in a heavily-male dominated working environment. However, Manako Kajii is like a train wreck you can’t look away from, and Rika finds her life taken over by her. She goes out of her way to taste the delicacies she recommends in an attempt to understand her psyche, and this creates an enormous lifestyle-shift for her – previously, Rika’s busy lifestyle and body-image-consciousness had left her with no room for the pleasures of food. However, while in Kajii’s orbit, Rika finds her appetite expanding, like never before.

While this book is about a possible-serial killer and based on a real case, one would be disappointed if they go into this expecting a conventional mystery, or a thriller. Rather, the strength of this book is its social commentary, on a number of topics, especially pertaining to womanhood, the workplace, and modern life, particularly in the Japanese context.

One of the themes of this book that critics have written about extensively is its representation and interrogation of toxic beauty standards, and the misogyny and fat-phobia associated with it. Prior to meeting Kajii, Rika Machida had exercised extensive control over her own weight. When sampling the delicacies recommended by Kajii, she finds herself putting on weight – only to face considerable social censure. Kajii, on the other hand, is well over the weight considered socially acceptable, and that leads to ridicule, with numerous people being shocked not so much at a woman seducing and murdering men, but at the fact that said woman was not thin, and ‘beautiful’ in a conventional way. A passage from the book goes as follows, “what the public found most alarming, even more than Kaijii’s lack of beauty, was the fact that she was not thin. Women appeared to find this aspect of the case profoundly disturbing, while in men, it elicited an extraordinary display of hatred and vitriol”.

Despite contrasting worldviews, Rika is clearly impressed by Kajii’s lack of concern for her weight, and how she unapologetically loves food.

While the discourse surrounding this book is often focused on food, feminism and fat-phobia, it also tackles another pernicious issue: work-life balance and modern-day loneliness. While Rika’s austere diet is partly a result of her commitment to maintaining her weight, it can also be partly attributed to her lifestyle, with her work rarely giving her time to cook. When she visits her friend Reiko, a housewife, she finds herself envious of her husband, Ryosuke, who gets to enjoy his wife’s elaborate cooking every day.

At one point, she compares herself to Kajii’s alleged victims, wondering if loneliness would, make her, like them, a vulnerable target someday, in this passage,

“perhaps I’m lacking in compassion because I’m still physically fit and capable of working, Rika thought to herself, trying to adopt and even stance on the matter. After the divorce, Rika’s mother had raised her single-handedly, and Rika was aware that she was perhaps overly aligned with her mother’s perspective. But it was possible that she herself would spend her old age alone, neglecting to take good care of herself–she might even have the wool pulled over her eyes by a younger man and have everything stolen from her”.

Overwork has been a long-standing concern in Japanese society. There is even a word –karoshi – for the phenomenon of people dying because of overwork. The work culture is often cited as a reason for the rampant phenomenon of loneliness in the country, since it leaves people with little time to cultivate personal bonds. Of course, rising loneliness is not unique to Japan–statistics show that people are now increasingly lonely all over the world.

But it has been particularly pernicious in Japan, where you see a drop in marriage and birth rates in contemporary times. When people do marry and start families, balancing work and familial responsibilities become difficult, which is why many women – like Reiko, Rika’s best friend, often exit the workforce. Reiko used to be a successful professional in the PR field. But she decided to quit work to focus on having a baby with her husband, Ryosuke.

In the context of an intense work culture, rampant sexism, and increasing loneliness, it is easy to see how one can be drawn into the worldview of someone like Manako Kajii. Kajii is a woman completely unapologetic about her appetite and her love for pleasure. Her life prior to her arrest was one full of the finer things in life—a stark contrast with Rika. She also spews misogyny, claiming that it is the nature of women to want to serve men, and that women’s place was at home, not at the workplace. There are two things I can simply not tolerate: feminists and margarine, is the most often quoted line from the book, one that also embodies the wit and humour present in it.

Kajii’s misogyny reminded me, in many ways of the ‘tradwife’ genre of influencers on the internet. Tradwife influencers preach a return to old-fashioned gender roles where the woman stays at home, cooks, cleans and submits to her husband. They present an idealized version of domesticity, while also often ranting about feminism and modern women. There have been several opinion pieces on the topic that speculate on the appeal of those influencers, and of the tradwife lifestyle general. One common theory is that in late capitalist socities, many women (and men) do not find it fulfilling to spend long hours at work, and the idea of getting to spend time at home engaging in domestic tasks might seem appealing in contrast. Of course, reality is rarely so rosy – and those influencers rarely present the less-fun sides of domesticity. However it is easy to see why people get taken in by them–and Rika gets taken in by Kajii’s words in a similar way. While she never fully gives in to her worldview, particularly when it comes to her opinion on women, she goes to great lengths to appease Kajii, and experience the things she extols.

This section of the book is of course, replete with mouth-watering food description, such as this one,

“The next course to be served was a chilled dish of avocado and snow crab stacked delicately like layer cake, topped with a generous helping of caviar……The two perfect squares of butter on top were beginning to lose their shape in the clear broth, their outlines blurring messily. Beneath them floated the crinkled noodles with their potent yellow hue…..Aside from the wreaths and candles, the only decorations here were three flame-shaped biscuits, and a sprinkling of ground pistachios and walnuts.”

While this book is presented as one about Kajii, a serial killer, the covert focus of the book remains Rika, and her own personal journey. There have been a number of recent books about women’s relationship with food, such as Melissa Broder’s Milk-Fed, and Lara Williams’ Supper Club. Butter is an excellent new addition to the list. Butter deals with women’s relationship not just with the consumption of food, but also with its preparation, and with the idea of domesticity in general.

The women in the book—from Rika’s mother, a divorcee, to Rika herself, Reiko, and even Kajii–grapple with food, and everything associated with it, in different ways, as seen from the passage below:-

“What does that mean, anyway–to be domestic? For a taste to be “domestic”, a woman to be domestic,’ Rika murmured. She did not know whether or not Hatoko was listening. ‘In today’s world, when there are so many different forms the family can take, it doesn’t really mean anything.”

And much of Rika’s story is a prelude to this realization. Over the course of the book, Rika learns to live a gentler, healthier life that does not unjustly compromise on her appetite. She also learns to combat loneliness through the company of her friends and colleagues.

Manako Kajii is in a way, everything Rika was not when she met her. She was ‘domestic’ while Rika was a career woman who rarely spent time in the kitchen. Rika led an almost ascetic lifestyle, while Kajii loved luxury. Yet, in a way both of them had a lot in common, and through Kajii, Rika realizes what she was missing out on.

In the end, she falls short of imbibing Kajii’s twisted worldview, and instead carves out a healthier path for herself.

Nileena Sunil is a lover of all things literary. She has had her work published in York Literary Review, Borderless Journal, The Chakkar, Setu, Kitaab and the anthologies ‘The Collapsar Directive’, and ‘Flash Fiction Addiction’.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates