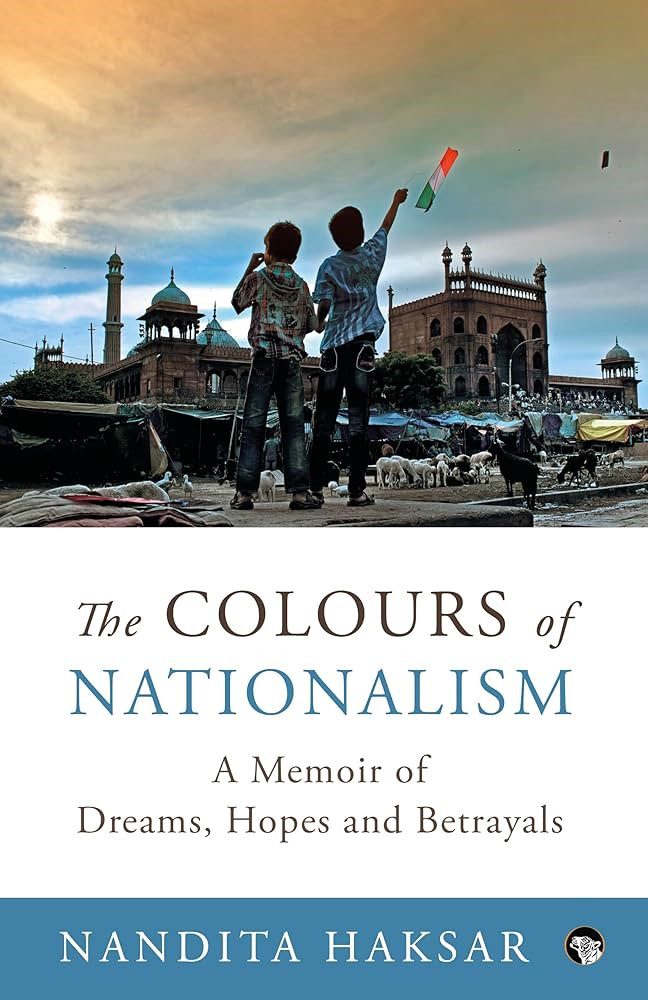

In her second volume of memoirs ‘The Colours of Nationalism, a Memoir of Dreams, Hopes and Betrayals’ the master chef, Nandita Haksar, serves a smorgasbord of her encounters with the law and politics ranging from an attempt to prevent privatisation of telecom services to coal miners seeking to get their mine nationalised and the Naga survivors of torture by the security forces.

With experience as her base, the proud patriot, Haksar brings conceptual clarity to terms like Nationalism being bandied about in this age of social media. It is a deep analysis of the way different sections of people experience nationalism and what it means to be poor, oppressed and exploited.

Published by Speaking Tiger and only recently launched in the market the book is almost a recounting of the history of post-Independence India and its efforts at building a nation based on equality and justice. Unlike academic books Nandita Haksar coaxes theoretical understanding from her experience and the telling of significant tales of struggle and courage.

Self-critical at times, reflective throughout, Haksar gives us glimpses of the relationship between politics law and the state.

Excerpts from a conversation with Anjali Deshpande

Anjali Deshpande: The elaboration of the title itself is a teaser. ‘Dreams, Hopes and Betrayals’. These are betrayals of ideological understandings and commitments. They come up as some deficiency in the understanding of how to go about building the nation of dreams, in which everyone is an equal citizen, diversity flourishes without getting in each other’s way. Only sometimes they arise out of petty politics of ownership of organisations and institutions. Congratulations for writing such a deeply thought-out memoir. A personal journey that also is the journey of a newly independent country that started out on the path of nationhood based on equality and justice and mostly did not succeed in the endeavour. You look back mostly with dismay.

Nandita Haksar: It is interesting that you say I look back in dismay. I feel that dismay and disappointment are emotional terms for understanding. You may be disappointed because one person did not get justice. That may happen. But you are not shocked out of your wits that you did not get justice. Nor do you go into depression which a lot of women did because they didn’t get justice but they did not understand why.

Actually, I look back with a sense of nostalgia and a certain pride in what our generation tried to do. In the book I look back critically because I feel what we must pass on to the next generation is our understanding from our mistakes so that they learn from them but uphold the basic values which I think were right and have stood the test of time.

As for the title, it indicates how nationalism means different things to different communities depending on how they experience India.

AD: Your memoir is like a ringside view of history of post-independence India. It records many encounters with people we read about in history textbooks and many of whom you address as uncle. Almost all the greats including Chacha Nehru are in it. You were seldom intimidated by them even though you kept your opinions to yourself many times.

NH: Our generation is the last one which had links with the Indian freedom fighters. There were those whose family members went to jail or suffered because they took part in the anti-colonial movement. Our family was nationalist but did not take part actively in the movement. I sometimes envied those who had been closer to those who took part in the movements.

AD: What I notice is that right from childhood you had a strong anti-colonial mindset and a questioning mind. You credit this to your parents who encouraged you to think for yourself. You also seem to have had a clear conceptual framework right from the beginning that evolved with your experience of all the movements and campaigns. Your ideas on nationalism have an empirical basis that is generally missing in the academic debates on the issue.

NH: Yes, it was a clear conceptual framework which had to be constantly readjusted as I engaged with very different movements. The book shows how the clear conceptual framework based on Nehruvian ideas did not include an understanding of patriarchy, of movements for national self-determination or caste. The struggle has been to fit these aspects of our national life into the original framework and when it did not, I was led astray into identity politics.

This is a system that will not give justice to the poor. I had no illusions about it. But what I did learn from experience in the 1970s that in almost all the cases of women, they were not getting justice. I have not discussed it in the book and I did not do many of those cases. One, I was not a feminist so I had no understanding of patriarchy in the judicial system. Women, when they approached the court, almost always lost and they were despondent and dismayed throughout. All over India. You can ask those who did the case work. From 1979 to 1986 I saw how it worked. I understood it for the first time and I wrote that book in 1986. (Demystication of Law for Women. A graphic book.) That was mainly before I became a lawyer. After I became a lawyer, I understood more theoretically how patriarchy works. How the criminal justice system and the Constitution are rooted in patriarchy.

AD: You participated in almost every campaign and movement for equality. You engaged with trade unions seeking justice. You give details of how workers tried to get their coal mine taken over by the government and lost the case. Similarly, an attempt to prevent the privatisation of telecom services met with failure in the courts. The case of Nagas tortured by the Security Forces is also a case that met with just a limited kind of victory. Despite that you say that there is no dismay?

NH: I think what comes out clearly from my book and my experience that our society is class based and working-class people cannot get real justice from the legal justice system rooted in class. However, there are possibilities to win small but significant victories to help the movement forward. I hope my book shows the complex relationship between law and politics.

https://www.newsclick.in/Coronavirus-Biological-Warfare-GCMU-Project-Smallpox-Pandemics-Politics

Knowing that you cannot get justice for the poor we did those cases and certainly my class perspective was sharpened in the process of doing those cases.

In the Naxalite movement for instance or specially in the M-L groups (Marxist Leninist groups) they would say ‘we don’t have faith in the system so why should we go to it (courts)?’ There is no question of faith. It is a question of understanding. How do you relate to the system. Either you lead a class struggle which is outside the system or if you are in the system how do you engage with it.

Like in the case of the coal miners. They were asking the government to take over the mine. Someone in Bihar went to court. They lost. Perhaps they did not use the right arguments. If you want, I can go into the principle of promissory estoppel. It is a technical point. It is part of bourgeois law, and it comes from the law on contract. To use it in the case of workers, which I did, would also mean how to creatively engage with the law. There is no question of disappointment. You are not going to bring a revolution through a court case. You can’t bring about a basic change through the legal system. I was very sure of that. My understanding, of how the law works and my articulation certainly grew and is still growing. I am able to theorise upon and articulate what is wrong or right about the system. That is why I am still alive and writing while many people just burnt out.

In case after case after case that they did they were not getting justice because they did not understand the State, they only understood the community. The women’s movement was dealing with violence within the community not the State largely. So, the family as a patriarchal structure was being propped up by the State. This relationship they did not understand.

AD: If you are so sure of it why go to the law at all?

NH: I hope my book shows and I can imagine that most people may not fully understand it unless they read it carefully because they have to have a critique and Marxists have not produced many critiques of the system and law. There is the debate about whether law is part of the super structure or of the basic structure, which I didn’t go into in the book because it is not a treatise.

If you look at it carefully that is what I am trying to say again and again. Understand the relationship between politics and law.

For instance, why do you write about poor people? Whom are you writing for? Even if they read it, it won’t change anything. You write because whether poor people read it or not, and they may be reading it too, and others read it too, they become aware. In the same way when we engage with the law, we should engage in a way that will expose its limitations. We also do take advantage of some little remedy that we may get. For instance, one of the things we do get, we used to get from the law is that when people were arrested, they could be saved from torture. I saved people from torture or I saved people from death penalty which is not a small matter. These are some of the things we could get.

There is the question of how you get it. If you feel that you are part of a movement then different people do different things. Writers write. There are people who write songs. There are people who organise. And there are people who do the law. So, I have said what my engagement with the law was.

I mention that the National Lawyers Guild of America which was an organisation of communist lawyers during the Mcarthy era so they fought. You can’t say, let them die. You fight. It is a tough thing because here in India you do it largely alone but there in the US it was an organisation and there the lawyers were trained to give certain arguments, to develop a certain kind of jurisprudence that will help the people and the struggles. Therefore, you engage with it. Not because you think that you can bring fundamental change. In the women’s movement the lawyers were not developing any feminist jurisprudence. How far can it take you in a patriarchal society?

Anyway, historically we know that we cannot bring any fundamental change at any point. It is a point in history when it happens. At most points of history, we don’t bring fundamental change.

AD: There was a time in the 1980s and 1990s when the apex judiciary was being criticised for its activism. You look at PILs as a creative invention to help those with little or no access to the judiciary. Some have said that it was a means to short circuit the normal judicial process. What exactly is the difference between the two? Do PILs still have any relevance or use? How do you look at that criticism considering many of the cases that the working classes and others met with a silent death in the Supreme Court?

NH: PILs allowed concerned citizens and organizations to file petitions on behalf of the oppressed or exploited. It gave visibility to many issues even if they did not get real justice. In so far as the PIL helps to make social economic problems visible they are relevant and effective and so the public interest jurisprudence has been diluted and met with such hostility by the orthodox section of the Bar and Bench.

AD: You say that initially you were reluctant to help some Nagas because you were an Indian and they did not want to be part of India. Your decision to understand their issues and get into a dialogue with them built bridges between them and India. The bridge was so strong that many years later a young Naga came to you seeking help to approach the Supreme Court. Did you begin with some hostility towards them and did dialogue help you conquer that hostility?

NH: My engagement with the Nagas began in JNU when I discovered that a part of our country was under what was effectively martial law. I was not sympathetic to the cause of Naga nationalists but I did not support Indian state’s repression and military force.

However, when the Nagas went to court, in part because of my intervention and the Naga human rights activists were happy to get some response from the Supreme Court in 1983. I was happy that there was a possibility of democratically engaging with them.

However, after the case (Oinam case) when the High Court did not give a judgement for 25 years, and when it did it merely said the files were lost, I felt the Nagas were justified in taking their cause to the international community and I went to New York to take it before the Human Rights Committee.

This is the time when I did for a brief time become engaged with identity politics but then I saw how destructive it was and it had the effect of dividing the Nagas along tribe and sub tribe I realized that identity politics cannot play a positive role.

It was not an individual Naga who sought my help but the Naga human rights organization and later I was involved in the peace process.

AD: Where does your strong belief in dialogue and mutual understanding stem from?

NH: Temperamentally, I am an activist, an agitationist, if there is such a word or a fighter. But experience with all these cases I describe in the book has pushed me into understanding that while agitation, struggle and movement are essential and primarily ways to enforce rights they must be supplemented with dialogue, negotiation, and yes even compromise. Compromise is a question of tactics or strategy not of principles or values or even our ultimate goals.

AD: You seem to have participated in almost all the significant efforts to construct an inclusive India steering away from religious identities and trying to foster scientific temper. From Kishore Bharati to the women’s movement and subsequently the Naga issue that even refused to be part of India. You also encountered some upright officials who helped you in the cases you took up and at least one of them seems to have been killed for this audacity. What does individual romanticism contribute when there is lack of a sustained movement?

NH: In all movements for justice, including class struggles or feminist movement we need allies. We need to know who are our friends and who are not. And among the allies a section of the bureaucracy and the bourgeoisie whether among the intellectuals or business are crucial for the success of the movement. Even the success I did have in the court would not be possible without such individuals who gave me access to information or documents that I would not have got.

Yes, you are referring to N Surendra who gave us the administration’s accounts of atrocities committed by the Indian security forces during Operation Bluebird.

AD: You traversed a long distance from being a district correspondent in Hisar to a human rights lawyer and engaged with some of the most controversial issues. You say in the book that from the Jharkhand movement to the Naga underground you saw those questions as national questions at that time. You have revised your opinion. You now characterise them as identity politics. Can you please elaborate? Delineate the differences between nationalist movements and identity politics?

NH: I have partly answered this above. But identity movement is a movement which focuses on promotion of one identity; in case of Northeast India, it is a tribal identity based on race and many times religion.

I was attracted by the Naga national movement because it sought to build a Naga national identity by bringing together some 30 plus different tribes. At the same time the Naga national movement celebrated diversity within the Naga tribes. For instance, each tribe however big or small had one vote when sending representatives to the Naga Students Federation. It is a principle which is followed in the United Nations General Assembly.

But then there were two problems: the Naga national movement started to get divided along tribal lines; there was a division between Nagas in Nagaland state and Nagas in Manipur. There was a separate movement for autonomy of the Zeliangrong people for autonomy; and more recently backward areas in Nagaland want a separate state. It is true many of these divisions were promoted by the Indian intelligence agencies but there is tribalism within Naga society.

The second reason for my distancing myself from the Naga national movement is that the slogan Nagaland for Christ does not appeal to me. Just as I would oppose India becoming a Hindu state or Kashmir movement for Islamic state.

Third reason, perhaps the most important, is that an identity movement divides the poor people and ultimately promotes the interests of the middle class and the ruling class.

AD: One of your serious complaints is with the NGOs. You see them as devices that derail movements. Not your words but that is what I think you imply. Now that the NGO sector is under attack how do you look at their role today?

NH: Yes. I will deal with this question in my third volume, Deceptions of nationalism. I have written about it in Civil Society magazine.

The critique of the NGOs and their role in social change came from Marxists and Communists, especially in Latin America such as James Petras. In India it was Prakash Karat who wrote extensively on the role of NGOs as conduits for imperialism.

I agree with that view. The NGOs especially those funded by foreign funding agencies have their own agenda and they are not answerable to the people but their funders; often the funders are large corporations and even state.

But the attack on the NGOs by the present Government is on an altogether different premise. Today NGOs play another role as well, they provide employment and also provide space for small but significant democratic spaces for working among the people. It is that space which is under attack. For instance, foreign funding is crucial for some of the most vulnerable sections of society including women, Dalits and refugees.

The attack on NGOs is not strengthening Indian sovereignty because our economy is already linked to the world financial markets and this government is encouraging the corporatization of Indian economy and even culture. NGOs in this context provided an alternative space for some relief work.

AD: You have a gentle way of being critical of the views of some of the people you loved and respected like your father. You never lose the historical context but you also imply that within that context there were alternatives available that were not explored. You have seriously questioned the absence of Ambedkar’s books in your home library. You have disapproved of keeping Ambedkar out of history courses even in JNU. Do you agree that such prejudices or misread nationalistic interpretations for the rise of identity politics in India? Was the domination of academia by upper castes responsible for such imaginations of a nation that kept out certain socially oppressed sections like Dalits?

NH: Yes, you are right. The rise of identity politics is partly because of the elitism of the nationalists.

But there was also the role of imperialism and the rise of NGOs which promoted identity politics.

And we cannot say the oppressed do not have agency so the middle class among the Dalits or women and religious minorities too had a role in the rise of identity politics. It is important to remember some kinds of identity politics played a significant role in deepening our understanding of exploitation and means of institutionalizing oppression and class.

AD: You dwell at length on the issue of communalism in the book. You relate your experience of running campaigns for secularism, and of riots in Hashimpura and later in old Delhi. Do you think that the bhai bhai rhetoric we used in those days had very little impact and is now almost irrelevant? What in the nature of communalism has changed?

NH: There are various aspects to this problem:

AD: Does some semblance of justice depend on individual judges? Is the possibility of justice not woven into judicial processes? Is it a fluke rather than a system?

NH: I do not have disappointment or dismay with the judicial system I have a critique of it rooted in my experience of law practice of thirty years.

I do not think of the relationship with the judicial system in terms of “faith” or “fluke”. That is why I think the campaign for a Kashmiri Muslim teacher accused of conspiring to attack the Parliament led to an acquittal even though he was sentenced to death.

That is why a hijacker was acquitted.

I hope people will understand the complex relationship between politics and law so they are better able to engage with the state.

AD: Anything else you want to say about the book?

NH: I think that people are not going to read it with the depth it requires. A book is read in different ways by different readers for different purposes. Often times I have heard people, even the left, say that India is this or India is that. Like in my flavours book too, I dealt with it. A Gujarati may think that dhokla is Indian cuisine and someone form UP may not even have heard the name. That was my first book, and I wanted it to show how much prejudice we have even on the question of food.

Here we see how people experience nationalism and what it means to them. I have not used the word but even the left used to say that there is a mainstream and there are side streams. Are they? We didn’t realise what it meant and how do you define mainstream? I didn’t use it because it is jargon and has been done to death. I want people to see that if you are from Nagaland or you are a woman or a Dalit, or a public sector worker, what is India to them? How do they feel? Do they feel they belong or not? What is their contribution? If just this much people understand that is a very good beginning.

I am making a very large generalisation here, but I must say that there is very little literature about this. There is that light hearted book about the two sates by Chetan Bhagat….but very little good literature that deals with this diversity in its depth. We may have Hindu Muslim marriage in it but it is very superficial. The whole realm of culture doesn’t deal with it. It is still rooted in its little little pockets. Unless that happens, we cannot even understand each other. I am hoping people will see that. That is all I want them to see, how do all of us from different parts and areas of India perceive it. People from the same area may also perceive differently. People don’t understand that. I face that every day because they don’t have a concept of being able to see some things that is other than the point of view they have. To not understand what is not our point of view, may be it comes from caste, I don’t know. But there are very few people I know who can cross boundaries. That is all I want.

We cannot speak for the whole country. I don’t mean it in a post-modernist sense. It is not that we cannot understand. We can. If we wish to, we will understand so much more. Otherwise, we have the post-modernist and identity politics, that is each one for themselves. That is not my viewpoint. Identity politics is a problem.

AD: Now two personal questions with your permission. You and your husband Sebastian Hongray have put together an extremely significant book of interviews with the leaders of the Naga Underground. You have always had each other’s support. Please talk about this beautiful partnership a little. Just how much and in how many ways has the partnership helped your creativity and helped you evolve your ideas?

NH: Sebastian and I have worked together for more than forty years from 1982 to today. Speaking for myself I am lucky to have a partner with whom I can work together.

But it does not mean a lot of hard work does not go into making our relationship a success because we come from very different social backgrounds.

I sometimes joke that I am the ideal Naga bahu. If I was not so deeply involved in the fights for justice for the Naga people the relationship would not have worked. In many ways it is true that I did not marry a person but a nation!

I remember one woman from JNU saying she was fed up of her Kashmiri Muslim boyfriend only talking about Kashmir. I told her it was impossible to be friends with any community which is facing oppression unless one can feel like them; and that means sometimes suppressing a part of yourself

I have always acknowledged Sebastian’s role in my creativity but this role was not automatic. The most important thing is that love must be rooted in respect and perhaps it is important to like the person not only love the person.

AD: At one place you say that in the 1980s you were deeply unhappy and you could not share it with your comrades. This was the time when the women’s movement was in full swing. You did share your unhappiness with Shahjahan aapaa across class divide. A number of us share this kind of experience. For all our feminist viewpoints of all shades, we never did talk of love, sex or emotions. Do you think we supressed them or sublimated them? Or are suppression and sublimation two sides of the same response…that is denial?

NH: I really do not know about how other people; other women coped. Speaking for myself, I did not share with other feminists because I did not think of them as my friends. I also felt they were elitist and did not share the same world view.

Besides being a lawyer, I was doing many of their cases so had to be the strong one to give them strength and support.

Suppression, sublimation and denial are not the same. Suppression is when you feel you cannot speak out, mainly social pressure, upbringing, fear and of course denial

Sublimation, is often a way of dealing with oppression and in India it has been most often in the form of religious devotion like Meera bai or Lal Ded. In the case of political people, it is through politics. In my case it was just that. I immersed myself in politics and learnt to use my unhappy experiences to understand and empathise with other oppressed people.

That cannot be called denial.

I have always had a problem in the way the elite women would make the poorer women confess their problems etc but never shared their own problems. This was power politics.

Nandita Haksar is a human rights lawyer, teacher, campaigner and writer. Her engagement with the people of Northeast India began while studying in Jawaharlal Nehru University in the 1970s. She has represented the victims of army atrocities in the Supreme Court and the High Court and campaigned nationally and internationally against the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958. In her capacity as a human rights lawyer, Haksar has helped to organize migrant workers to fight for their rights and voice their grievances. In 1983, she became the first person to challenge the infamous Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) in the Supreme Court. She successfully led the campaign for the acquittal of one of the people framed in the Indian Parliament attack case. She has written innumerable articles in national dailies and journals and is the author of several books, including Nagaland File: A Question of Human Rights (co-edited with Luingam Luithui) (1984); Framing Geelani, Hanging Afzal: Patriotism in the Time of Terror (2009); Who Are the Nagas (2011); ABC of Naga Culture and Civilization: A Resource Book (2011); The Judgement That Never Came: Army Rule in Northeast India (co-authored with Sebastian Hongray) (2011); Across the Chicken Neck: Travels in Northeast India (2013); The Many Faces of Kashmiri Nationalism: From the Cold War to the Present Day (2015); and Kuknalim: Naga Armed Resistance (with Sebastian Hongray, 2019).

Haksar lives in Goa, Delhi and sometimes Ukhrul, with her husband, Sebastian Hongray.

Anjali Deshpande has been a journalist, activist involved with several campains and movemensts including the women’s movement and the struggle of Bhopal Gas Survivors for justice.

She is a bilingual writer. Her first novel Impeachment (Hachette India) was published in 2012 and its recreation in Hindi titled Mahabhiyog (Rajkamal Prakashan) was published in 2016. A collection of her short stories in Hindi, Ansari Ki Maut Ki Ajeeb Dastan (Setu Prakashan) appeared in 2019.

Hatya (Rajpal and Sons) the original novella of this translated version was also published in 2019. It has been translated and published in 2023 as Mord. (Draupadi Verlag publisher) and Nobody Lights A Candle in English by Speaking Tiger this year.

She is the co-authored a non-fiction book on the Struggles of Maruti workers with Nandita Haksar. Factory Japani Pratirodh Hindustani in Hindi (publisher Media Studies group) and Japanese Management Indian Resistance in English (Speaking Tiger) were both published in 2023. The book is being translated into Japanese.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates