Kabir Deb: The voices in a writer’s head are considered as the source of what they want to document. But there are voices which cannot be documented. In your case, what do these voices say and mean to you?

Devashish Makhija: Yes, there are voices in my head. Often, do not translate easily into words on paper, but these are voices that do not have sharp edges around them. They are probably sounds, emotions, impulses and triggers, and they crackle. The kind of crackle that causes us unrest and rage, a shivering kind of resentment to the way the things are in our world and these really have been the instigators and the impulses and the triggers to create tell the story, or at least, I tell. And often these triggers have one or three of four of the primary things that move me or I am obsessed by or are prerogatives that I am drawn to.

They can one of them or they can be a combination of all of them, but it often boils down to these impulses that emanate from my resentment towards the inequality in the world we live in. The thing that really affects me is how those who are born or handed power tend to draw the lines to or mend the rules for those who are born out of power. And here I am not talking about human beings exclusively. I am talking about the other residents of planet Earth. The other thing I am really obsessed with is the idea death and the way it moves me, affects me and makes me curious to know me, and I have explored death in all kind of way including a comic way. And the third is sex. All the complicated equation that we have with sex, individually and as a society. Even today, the mention of the word becomes this initiator of discomfort in all kinds of rooms whether it’s a room full of people bound together by religion, politics or some sort of a social circle. Gender or given the absence or fluidity of gender, sex still is a tricky and precarious thing to talk about and it is something that moves me to talk about it in some way or the other.

KD: You’re predominantly a writer. But mostly, people know you as a filmmaker. How does writing help in the process of portraying a motion picture? Also, how important is it to explore multiple platforms?

DM: This is something that most filmmakers do not want to talk about but it’s a truth that I feel that filmmakers cannot side-step a circumvent. All the greatest, most compelling, most moving filmmakers across history have also written their own material and there’s often a misunderstanding regarding writing a film. Writing a film doesn’t need you to be a writer, you do not need to have a command over language or grammar, metaphor or symbolism through words or texts. Writing is simply putting what you are feeling or seeing or exploring what’s inside your head in terms of sound or image on two people so that you create a roadmap. Literally creating a map through unchartered territory to figure out where you want to land-up. You can then a hundred people on the journey, which is otherwise impossible to share with anyone else what’s going on inside your head. I always contest writing a film although I believe in language and its elements even when I am writing a film. But every competent filmmaker who has a voice need to put into paper what they seek to achieve with sound and image. In the times of Jean-Luc Godard, if you see his script, it is literally just squeals and doodles and dialogues and direction. It is a scrapbook. Satyajit Ray, yes, he must have written his dialogues quite lucidly and eloquently and good writing on paper because he was a prose writer himself, but there was a lot of communication that he did on paper through drawings and almost storyboard kind of drawings but not really storyboards either.

Just using the images to write on paper. So, writing a film can be interpreted in many, many ways. It is not really writing, but because I enjoy words and expressing myself through them, by default I inhabit multiple mediums because I don’t get the satisfaction of the writing process when I am writing films because that’s the first very, very preliminary in the making of a film and after it is done once I enter the process of production and shooting a film, I am leaving the writing world behind and we are starting to let the world that we visualized in the form of shooting. The former becomes less important. So, the eventual world product is so far ahead and so far above the written world, that the written world usually is not the most important element in the making of a film. So, I enjoy prose because the written world is the final destination.

KD: In your film Bhonsle, the characters have their own world, and they come together to showcase the situations we do not want to be in. The factor of divisive politics and an offensive monopoly is what you make us understand through the film. How different was the entire process of writing the film before the initiation of portraying the reality we are living in?

DM: Bhonsle came from a very personal experience in 2006, when I had come to Bombay, even before that in 2003 when I was researching Black Friday, a lot of police that I was trying to talk to, trying to get information out of it’s almost like they are being instructed by the Shiv Sena, but predominantly it was the Maharashtra Navnirmaan Sena (MNS), which was sort of picking up steam and becoming a little hardcore about the insider vs. the outsider and there was strict order to all government employees to talk in the language of the state, and in signboards across the city, the names were being changed into Marathi and I had just come to Bombay and to speak to a cop in Hindi, and to get answers in Marathi, a language I was struggling to understand, was extremely irritating and rage inducing. Although we know the Constitution clearly says that in India I can reside in any part of the country, I can speak my language and learn a bit of their language but I cannot be made to feel unwelcomed. And that strange bigotry sort of stayed with me. In many ways, I struggle with my sense of ruthlessness and I don’t really have any place in terms of my culture, my mother tongue and I don’t have a homeland that I want to or seek one. But when I want to express myself as a story teller I don’t really have my own stories because my parents came from, what I now known as, Pakistan, I was born and grew up in Calcutta and my mother grew-up in Bangalore, so then I am working in Bombay, and they are three different states with three different cultures and languages, which are my own.

But when I tell stories, I don’t have any local root, any cultural depth to draw from. So, from very early phase as a story teller, I sought to look for stories outside of my own experiences and roots. So, when I came to Bombay, I was made to feel this way, it shaped me, it shaped my story telling voice because Bhonsle came from that very protest, it came from protesting against that very behaviour and that’s something that informed all the many subtexts, metaphors and layers of the film. Even when there is the relation between the two neighbours, and Bhonsle and Sita slash Lalu, when it is Bhonsle’s sense of inner displacement from his own life, a life he does not want to live, and rather die on duty. These are all ideas of displacement and rootlessness and not being able to find an inner centre to your person. And all of this, from the minute I came up with the idea to jamming with my co-writers to the communication with the actors to the shaping of the film bit-by-bit, these core feelings sort of informed all those decisions where I spent a lot of time communicating these inner things at the fulcrum rally of my films to everybody, again and again, so that everyone hopefully by the end of it understands that it is operating from that very core.

KD: You’re a man of language. In ‘The Savage Detectives’, Roberto Bolano, through Juan García Madero, gets to speak about how the conventional way of writing about stuff is still maintained, but the oppression/censorship of write-ups gets updated using various ways to censor the art form. We are living in a time where the Indian audience is not rooting for a single language. Do you think it is the reality? I am asking the question, since in literary meet-ups and also during film festivals, we get to see polarisation, with respect to the language of the powerful ones or to be precise, rich and well-connected people.

DM: I don’t know if I am a man of language to begin with, I have a very conflicted relationship with the fact that I operate in language I can express myself in, I think quite strongly through language but I also believe language is the root cause of all conflicts, all human conflicts, regional, national, religious, class, caste and race conflicts. Almost all conflicts boil down to two entities speaking two different languages either not understanding each other completely. If we did not rely on language and rely on image, sound, music and feeling, we would probably be a more, I don’t like the word but for the lack of a better word, tolerant species. We would be a less complex and greedy and ownership obsessed, because with language comes the idea of belonging somewhere, species. And since I am rootless and do not know what my own stories are, I also have tended to not feel too kindly about the idea of language. Yet ironically, it is the one medium I find myself resting more strongly in. so, I agree that in all kinds of social and artistic gatherings, and not just gatherings, rather in these circles, these ecosystems and these economics, they are the ones with the most money and therefore, the most power who will decide which language is going to override the other. For example, this is something more unknown in India, but we are the ones with more than 19,000 tribal dialects and this country will not, at least today, will happily not acknowledge it because we are in this juggernaut of trying to make Hindi override every state language. So, who’s going to think about these tribal dialects? I forget who said this but there is one quote that says that a dialect is simply a language with a gun to its head.

All these 19,000 dialects, at one point, were languages but less and less people spoke it generation to generation, and slowly they became dialects, and then slowly they’ll become extinct. And all of these ideas tied to one another made the powerful section rise and the stamping out of the marginalized or the oppressed section. Through language, they then wheel power over those who speak the lesser spoken language. So, yes, all of these things I am bothered by and I toy with and therefore, my films are trying to bring in a sense of a conflict of language. Like in Bhonsle, the Marathi inside and the Bihari outsider, I would have wished to make this film in Marathi, but I didn’t find a producer. So, I was compelled to make it in Hindi. My other films like Oonga and Joram deal with the same situation and the polarization cannot be bridged because the minute you see a person speaking a different language, the surface gets uncomfortable.

KD: I won’t ask you to recommend books, but the shade of Coetzee and Camus is quite evident in your works. Could you take us on a tour to meet your favourite writers from the past and the present?

DM: So, yes! I own books by Camus and Coetzee, but I am yet to read them, shockingly. I read very little because I have trouble with my eyes and in the last twenty years, I have written so much that has not seen the light of the day, I just kept writing and writing and writing and so, the time to read just diminished more and more. But the writers who shaped my style, choice and syntax are Ernest Hemingway, although he was a misogynist man but some of his short stories tended to dissect the human condition and affected me. Dashiel Hammett was yet another writer whose sharp sentences has also influenced my thought and writing. And Paul Auster had a hypnotic influence on me since he goes on the tour of an abyss of the self within the self. Although his themes and subjects and characters are nowhere similar to my own world but there’s something in his writing that shaped me what I do or try to do with my characters and stories.

KD: Your movies stand out for the non-fiction they portray through a fictional world. It has always been the way to release the emotions of the artists. Even after watching all your films, I still feel haunted by your short film, ‘Agli Baar’. What is non-fiction of the present time and how do you address the situations when you’re not making films or writing books?

DM: So, it’s a strange thing but a lot of people who have seen Agli Baar in the past, they always used to refer it as my own short documentary. I had to keep reminding them that it is not a documentary. It has actors and is rehearsed and has a constructed reality. Although it borrows heavily from the reality. Even my films like Cycle or even Joram, my current feature film, people often get the feeling that they are watching a documentary. This is also because of the way I write them; I borrow heavily from the real world. I fictionalize them but I am also working hard at setting stories and the characters in the real world since it has affected me to write those stories so that the distance between the fictional world I am creating and the world where it was playing out reduces further and further. Coming to your question about how I address the situation when I am not writing books or making films, there’s a reason why I make such films. The situation just enters in me like a snake and start feeding on me and strangely, the flesh and skin of the snake start blending with mine. So, if I don’t turn them into a book or a film, the snake would just keep on eating me from the inside. Thus, I have an abusive relationship with my work.

KD: How important is it to give a place to anger whenever we are trying to nurture something that’s against the foundation of fascism (small or big)?

DM: My initial impetus towards making anything or tell a story is anger. Anger can be misdirected and can become violent (physically or emotionally). But if directed properly, it can explore new avenues. It acts as a fuel towards everything I have to say. Every little choice of my frame or character or the dialogues that sprout from them is influenced by anger. All my stories have come from a place of discomfort about something I feel is not right and needs to be rectified. From the government we choose or the culture of inequality we try to appropriate has always driven my anger and the stories I write or portray are a reflection of that only.

KD: Joram has been receiving every possible crown at different film festivals. The importance of festivals is so visible whenever we mention films like Omerta or Joram. It is very important that a director should receive appreciation in the form of monetary benefits from the mass audience. Is it possible that films which speak about the bitter reality would be accepted properly in the near future?

DM: Joram released in the theatres and has been brutalized at the box office. It has sunk without a trace despite getting the most critical acclaim arguably that a film in India has got in the past year. But the film didn’t translate into footfalls and eyeballs. So, I don’t have a clear answer to this question. My films have always gotten a critical acclaim with the best awards and reviews possible but when it comes to being watched, outside of the film circuit, when someone has to pay money to go and watch them, the situation doesn’t get translated because my films do not entertain. They do not let you forget your worries for the while they are being portrayed.

I always hope they wrap you on the nose and remind you of the actions you’re doing wrong, and I think people going into the theatres don’t want to be made to feel that way, except when you are in a film festival. My films aren’t the films that you can watch unsustainably by watching over-expensive popcorn, being cooled by unnecessary air-conditioning because my films question the exact thing when you’re watching them. I don’t the answer to this question. I would just say that I am broke and I don’t own a cycle since I cannot afford one. I still share a small house with an actor who is over ten years younger than me. I have lived like a hermit and perhaps, I have actively lived these choices to empower the stories I tell, and the films I want to make. But there’s a strange paradox in me. I do want monetary benefits from my film but at the same time, I realize that films aren’t made for money. It is just meant to leave the best carbon footprints on this Earth. Yes, if I would have been born a hundred years back, I might have chosen to be just a painter or a novelist and never a filmmaker.

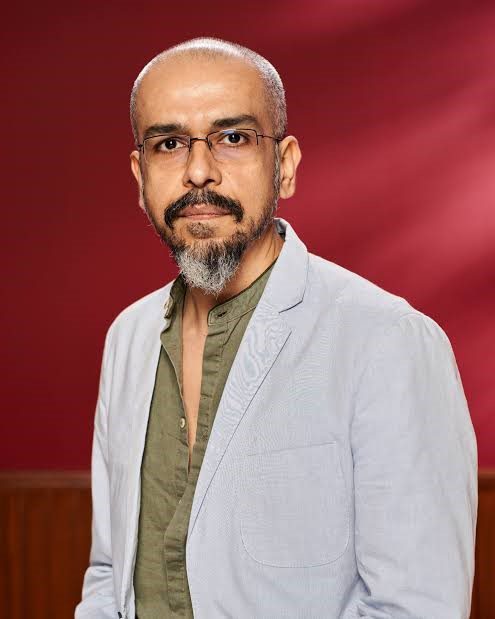

Devashish Makhija has written and directed the full-length award-winning feature films like Joram, Bhonsle and Ajji along with numerous other short-films. He is a multi-practice artist. He has his own solo art show ‘Occupying Silence’ and is a prolific writer, having written the bestselling children’s books ‘When Ali became Bajrangbali’, ‘Why Paploo was Perplexed’, ‘We are the Dancing Forest’, and the multiple award-winning YA novel ‘Oonga’.

Kabir Deb is the interview editor of Usawa Literary Review.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates