Kabir Deb: Hey Kynpham! I hope you’re doing well. Firstly, I want to congratulate you on your wonderful book, Funeral Nights. So, my first question is related to the core of the book. How important do you feel is the folk culture of Meghalaya to understand human existence and the country we live in?

Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih: Hi, Kabir! I’m well, thanks. I hope you are, too. By the grace of God? The protagonist in my new novel, The Distaste of the Earth, says, ‘But my supreme bliss came when I unyoked myself from God.’ Just a thought.

It is not so much the folk culture of Meghalaya, but the world view and religious philosophy of the ancestors of the Khasi people that can contribute a great deal to the understanding of our existence on earth. And this is not just an empty claim. I will direct your attention to two aspects of this philosophy written about in Funeral Nights, although there are more.

Firstly, According to our khanatangs, the sacred myths, Khasis believe that U Blei Nongbuh Nongthaw, God the Dispenser, the Creator, whose form we cannot even begin to imagine, for that is forbidden, creates everything. His first created being was Ramew, the guardian spirit of the earth, and her husband, Basa, followed by their children, Sun, Moon, Wind, Water and Fire. Their combined efforts turned the planet into a pleasant and plenteous land, teeming with all sorts of living things.

Unlike the other theories of creation, Khasis believe that man was originally an inhabitant of heaven, living with all his kith and kin under the benign guidance of God and his serving spirits, sometimes referred to as the gods. His coming to earth was because of Ramew’s pleading. Thus, besides telling us about the creation of the world and the beginning of life on earth, the myths also emphasise one crucial aspect of the Khasis’ religious thinking—the concept of ïapan, or pleading.

This concept points to the belief that man was sent by God to become the caretaker of the earth, and therefore, he cannot act as the master of everything he finds on it. God is the Dispenser and Creator; for that reason, man has to plead with him, to ask him for everything he needs, from the smallest to the biggest. This is crucial. The Jews, for instance, believe that God made man so that he might populate the earth with his countless hordes. ‘Go forth and multiply,’ he said. This assertion places man at the pinnacle of all creation. In other words, it argues that man is the master of the earth, while all other creatures are here to serve his needs and his goal, which is to multiply. This kind of anthropocentrism encourages man to indulge in all sorts of earth-wrecking activities in the name of progress and development. He tears down trees in the forest; he quarries the earth; he destroys hills and rivers, land and sea, earth and sky, and thus places all species of living things, himself included, and the entire planet in terrible danger.

But the old ones who formulated Khasi thought, in their compassionate wisdom, stressed the fact that man was sent to earth by God, not to multiply himself, but to be the honourable carer that Ramew pleaded for. Khasis do not believe that man is the crown of creation. To them, everything that breathes, and even those without life, like sand and stones, are equal creations of God. That is why the Khasi stories always begin with, ‘When man and beasts and stones and trees spoke as one’. The universe is a cosmic whole that receives its animation and force from the one living truth—God, U Blei. Because of this, the old Khasis held nature in great esteem. They never indulged in acts of wanton destruction. When they went to the forest for tree-cutting or hunting, they bowed low and explained themselves; they prayed and appealed; they asked and pleaded before God.

Do you see how important this kind of anti-anthropocentrism and strong connection with the land are to our planet? Lynn White Jr., the pioneering ecocritic, argues that the environmental crisis is fundamentally a matter of the beliefs and values that direct science and technology; he censures the Judeo-Christian religion for its anthropocentric arrogance and dominating attitude towards nature. Another pioneering ecocritic, Cheryll Glotfelty, tells us about how ecocritics and even eco-conscious theologians are turning to ancient Earth Goddess worship, Eastern religious traditions, and Native American teachings. And why? Because, like Khasi religious philosophy, these belief systems ‘contain much wisdom about nature and spirituality’.

Secondly, the old Khasis gave us Lai Hukum, three all-embracing commandments, including ka tip briew tip Blei (the knowledge of man, the knowledge of God), ka tip kur tip kha (the knowledge of one’s maternal and paternal relations) and ka kamai ïa ka hok (the earning of virtue). I will refer only to the first commandment, and the first question I will raise is why ‘ka tip briew’, the knowledge of man, is placed before ‘ka tip Blei’, the knowledge of God.

The Khasi myths make it clear that man was sent to this world in accordance with Ka Hukum ka Kular, the commandment, the pledge. According to this pledge, God wanted man to lead a happy and peaceful life on earth, in harmonious and respectful relations with his fellow men. The knowledge of man points to this stipulation. If man was sent to live on earth with other men, what must he do to be happy and tranquil? How must he work and earn his livelihood? How will he be strong? How will he prosper? How can he organise his feasts and celebrate his festivals, if he cannot live in harmonious and respectful relations with other men? If he is dominated by the evils of greed and envy, his life will be full of quarrels and disputes, clashes and conflicts. And his way of life will not thrive, it will shrivel and decline, and the society as a whole will weaken and collapse. God is above, but his fellow man is on earth, and therefore the first duty of man is to know, to respect and love his fellow man. Only this can bind men together in a functioning society.

In such a society, man must know both his rights and duties. That is what the knowledge of man teaches. If he’s not aware of his rights, others will take advantage of him, and if he’s not aware of his duties, he’ll become an obstruction to everyone. To know only one of them is not enough.

But in its deepest connotation, the knowledge of man forms the basis of all human actions. It teaches man to be prudent and urges him to ponder his every move carefully. Will it bring him happiness and joy? Is it good? Will it hinder others in any way and become the cause of ill will and conflict? Is it something that he has to do, no matter what? He thinks these things through—both the task and its outcome—and only then takes a decision on whether to proceed.

In this manner, a person guided by the knowledge of man is also guided by his conscience, which, by its very essence, weighs all things on the scales of virtue and truth. Therefore, a person blessed with conscience, or the knowledge of man, is also blessed with the knowledge of God, because God stands for virtue and truth. By placing the knowledge of man before the knowledge of God, the Khasi faith indicates two things. One, that man must serve God through service to his fellow man. In other words, service to man is service to God. Two, man must always be guided by his conscience.

Many religions lay too much emphasis on the knowledge of God. If we take a careful look at what is happening around the world today, we can see how dangerous this kind of teaching can be. The relegation of respect for man to an insignificant corner has been the cause of many conflicts. In fact, all the religious conflicts in the world, from the time of the Crusades in the thirteenth century to the present day, have come about because too much importance has been given to the knowledge of God. Such an emphasis without the knowledge of man turns everyone into religious addicts and ruthless fanatics, ready to kill and destroy for the sake of their religion.

But the ancient Khasis had already seen the harm that fanaticism could breed. Not only that, through their sacred myths, they taught us that God, U Blei, is the same for everyone, no matter which ethnic or religious group we belong to. Only the manner of worship is different. The God of the Khasis is thus also the God of Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Jews and Christians. And if that is so, where is the feeling of rancour between communities?

In a world too drunk with religion, don’t you think such a world view is of the utmost importance? For me, the religion’s humane anti-anthropocentric attitude and its lack of missionary zeal are truly admirable, though I’m not very religious.

KD: With the advent of a more neo-liberal state, Meghalaya has started to exude a very subtle kind of toxicity through its socio-political climate. Why do you think in a culture influenced by both the Western and Eastern traditions, we’re seeing such a perversion of ideals and incidents of violence?

KSN: The problem is that the people of Meghalaya, and the Khasis in particular, were not influenced by both the Western and Eastern traditions. When the British and the Welsh missionaries arrived here, they sought to implant a new past in the Khasi psyche, a past that had nothing to do with our origin, history, culture or even geography. The missionaries, for instance, actively discouraged people from having anything to do with their culture and their past but did everything to make them learn ‘the history of the diaspora and the holiness of unknown deserts’ by heart. And the influence of Western education and values made things even worse. So, as early as the 1920s, the Khasis had become what Professor Meenakshi Mukherjee would later describe of Indians in general, as ‘the exiles of the mind’. In talking about the Khasis of that period, S.K. Bhuyan, a prominent Assamese scholar, said, ‘They have been allured by the charms of the culture with which they have come into contact, and never perceive that there is good in their own’.

This is sadly still very true about many of us. We embrace modernity, with its development and progress, in a kind of headlong rush onwards. And worse, the unconscionable materialist greed innate in its neo-liberal doctrine seems to have gobbled them up completely. As I said elsewhere, I rue the fact that we have become so different: truly a generation kaba bam duh, one that eats till extinction.

I believe that modernity should walk side by side with tradition:

how hopeful to watch

hip-hops with falling pants

doing a traditional dance.

—Time’s Barter: Haiku and Senryu by the author

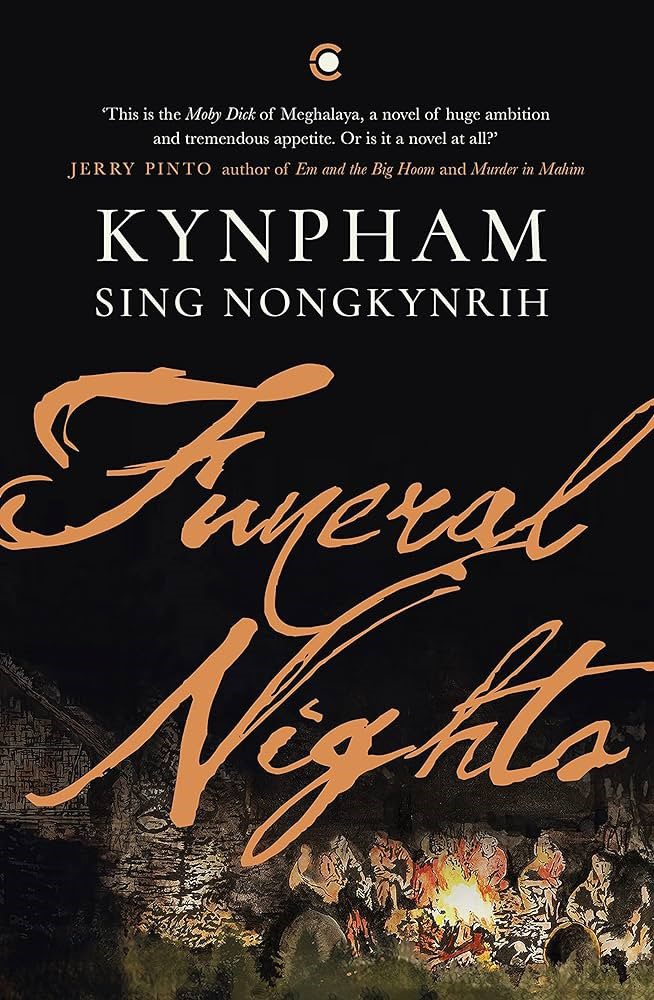

My hope rests with those young people who are reading up on Khasi history and culture, and who are rediscovering some of our traditional values. It is a great pleasure for me when youngsters are overheard talking in restaurants and boasting about how ‘They are now born-again-Khasis’ because of Funeral Nights.

Incidents of violence in Meghalaya and the rest of the Northeast are mostly related to insurgency and ethnic clashes. The growth of militant nationalism and insurgency whose demands vary from greater autonomy to outright sovereignty had started with the country’s independence and the integration of many of the tribal states into the Union through the Instrument of Accession. But this problem is much less in Meghalaya today. However, because the tribal communities represent a mere drop in the ocean of India, people feel that the threat posed by the influx of migrants from outside the country and the region is a very real one. Something has to be done about it, because when those concerned feel threatened, they may resort more and more to direct action. And that is a recipe for disaster.

KD: Your book sheds light on the importance of conversation & its mental construction. What are the ways through which we can make decent conversation a top priority when dissent/debate is being curbed by religious extremism and a ferocious linguistic bifurcation?

KSN: Here again, we can learn from traditions. In Funeral Nights, I learnt the importance of using searching conversations to discuss intellectual and philosophical issues from the Socratic dialogues of Plato, and from the Khasi funeral tradition—where consolers meet in a death house and talk all night—I learnt the importance of making conversations decent, humorous and engaging despite the differences that may exist.

Of course, it’s also a matter of decency. While questions of ethnic, religious and linguistic identities may be important, we should never allow these considerations to turn us into fundamentalists and fanatics like the ones causing all the conflicts in the world today. In a country like India, live and let live should be our motto. On national television these days, we don’t see debates but shouting and slanging matches—propagandists telling shameful lies. Concerning this issue, I think we should seriously revisit important Indian traditions like Vada, the honest debate.

KD: Death is the only reality of life, which has roots and shoots. What is your perception of death in the book? Also, how necessary is it to get a clearer idea of something so sad yet so real?

KSN: In answer to a question about why Khasi funerals seem like feasts, a character in Funeral Nights says, ‘Death for a Khasi is not a tragedy.’ Elaborating, he adds, ‘Of course, death is always a matter of great sorrow for the living, and if the dead person happens to be the sole earner in the family, that’s a real tragedy. But not for the deceased. We believe that the soul goes to eat betel nut in the house of God unless the person has committed a serious crime. This is another way of saying that, through death, man attains eternal life. The living draw consolation from this belief …’

My feeling is somewhat different. Death is the nightmare that haunts all life. For those who are old and alone, the fear of dying with no one by their side is a terrifying obsession. Death gnaws at them—and I speak from personal experience—like a monstrous bug, night after night, after night. For humans in general, too, death is a frightening reality, if not a fixation. So we use religion to create heaven and a hereafter, but notwithstanding that, we are always reluctant to let go of life: our blind faith in heaven can neither allay our fears nor console our losses.

It is only those constantly buffeted by the dark misery of life, only those repeatedly whipped by the wounding lightning strips of fate, without redress from man or God, who can say that death is the natural end of all sorrows and seek it out like a beloved:

Oh, I know! Death will replace you in my heart.

I will seek it out like a beloved:

every moment, I will seek it out,

for its loving embrace;

for its sweet, liberating kiss …

— “Death on a Birthday” by the author

Is it necessary to get a clearer idea of death, so sad yet so real? Writers, artists and philosophers have been trying to do that for ages. Existentialism tells us how to look at the human condition for what it is, an extremely ‘bounded’ reality. As James V. Baker says, we are bounded by birth and death; we are ‘in a fix’, situated, ‘at this particular time, at this particular place’. Time and space are our jailers and our strongest experience is ‘of time and of being headed towards death’. It takes great courage to face down such a condition and act ‘authentically’. That is why we seek to overcome the horror and absurdity of our existence in many ways, particularly, three: ‘through art, through love, and through religion’.

But despite the immersive experiences of art and love and despite the delusionary comfort offered by religion, it would still be difficult to lead a happy existence without the distractions of life. Just a few lines from Szymborska’s ‘Funeral (II)’:

‘so suddenly, who could have seen it coming’

‘stress and smoking, I kept telling him’

‘not bad, thanks, and you’

‘these flowers need to be unwrapped’

‘his brother’s heart gave out, too, it runs in the family’

‘I’d never know you in that beard’

Life is a great distracter. Even in the midst of a funeral procession, it will not allow us to dwell too long upon death.

KD: In the times we are living in, ideological differences have abused our fellow feeling to a very dangerous extent. In the past, we had a system that nurtured a diversity of ideas and opinions. What has made people so hostile towards the principles of diversity?

KSN: History has shown us that great disasters have often brought people together. Just one or two examples: after the Second World War, we established the United Nations (let’s forget for a while that it is dysfunctional and almost useless), and after the Holocaust, we raised the slogan ‘Never Again’. In our country, after the Freedom Struggle and the disaster of the Partition, we established a benevolent and tolerant secular nation.

Indeed, after the terrible trauma of a disaster, we tend to remember our common humanity and draw together. But then, our instinctive fear of the other, those unlike us, sets in again once we begin to perceive real and imaginary threats from them. These threats may originate from our basic differences, conflicts of interest, identity politics, unchecked mass migrations and so on. The rise of right-wing fascism everywhere in the world today has its roots in them. And fascism is worsened manifold by racist bigotry. We see this in our country, but the worst example is what is happening in Gaza, where fascism and racism meet colonial tyranny, unleashing before our eyes the most horrifying display of evil.

KD: On a trip to understand humanity, Funeral Nights speaks firmly and strongly on issues without fear of the consequences. In a world where everyone is self-seeking and hammering a nail, so to speak, to achieve their particular objective, is this practical?

KSN: It is true that in the novel, the characters grapple with a lot of tough and controversial issues—ethnic survival and communal violence, influx of illegal migrants, corruption in high places, uranium mining and dead rivers, pristine forests and their frightful decimation, deprivation and tales of woe, coal barons and criminals, militants and extortionists, the police and the protection racket, gangsters and the plunderers of democracy to name just a few. And they all speak without fear and equivocation. This reflects the deep artistic commitments of the author. The epigraph of the book, a quotation from Alexander Solzhenitsyn, declares that literature should be the breath of contemporary society and should be daring, transmitting the pains and fears of that society and warning it in time against threatening moral and social dangers. This is the kind of artistic responsibility I would like to uphold as a writer.

But in the eyes of ordinary people, this may not be a practical attitude. Some of my well-wishers gave me a lot of advice and even warnings while I was finishing Funeral Nights. One said, ‘If you write like this, the state politicians will never give you an award.’ Another said, ‘If you write about her corruption cases, this minister will come after you.’ Yet another said, ‘If you write about the militants, they will come gunning for you.’ I firmly believe that a book should be written without fear or favour. It should never be written like a propaganda mouthpiece. Even in the face of incarceration and persecution, a writer, if he is genuine, can do nothing else but speak the truth since he is moved by what he strongly thinks and deeply feels about, guided by his conscience, which, by its very essence, as I have said, weighs all things on the scales of virtue and truth. If he has an agenda at all it is always on behalf of fairness and justice. Any other considerations are like chaffs in the wind.

KD: Colonialism has been suppressing the folk narratives of the country for years. What is the one fundamental thing we have to do as individuals to keep this tradition alive and thriving?

KSN: You are right about the colonial suppression of folk literature. In the Northeast, for instance, the literary legacy of the missionaries was two-edged. While on the one hand, they gifted the tribes with a common literary heritage, on the other they made them deny the existence of their own literature in their rich oral traditions and turned them blind to the possibility of such an existence by teaching them to be ashamed of whatever was their own as something pagan and irreligious. That was why, for a long time, my compatriots never even thought we had a literature of our own. Because we became literate only in 1841 with the introduction of the Roman script used to cast the Khasi language in written form, everyone thought Khasi literature also began that year. But now people are at least aware that not having written literature is not the same as not having literature.

However, mere awareness is not enough. Our folk literatures must be actively promoted through books, print and visual media, and the curriculums of schools and universities. Even Funeral Nights was partly undertaken as a postcolonial project to counter the many misrepresentations and misinterpretations made about the Khasi people by colonial writers. One way to clear the ‘wounded’ name of my people was to use Khasi mythology, because I realised that in every myth is embedded the wisdom of the race and every legend speaks in symbolic overtones. As the Welsh had done in the 19th century, the one fundamental thing we should do is try to rehabilitate the past as high culture, everybody’s culture, regardless of our religion, and turn to our legendary heroes and mythology to provide a mooring to prevent our directionless drift.

Some detractors may indeed say we are too preoccupied with the past and its traditions. What I’m saying is that the present should have a symbiotic relationship with the past. The present must be guided by the lessons of the past and draw its sustenance and strength from there as it journeys into an uncertain future. But for the past to be able to do that, it must be treated with filial love and reverence, for it is not something dead and ‘best forgotten’. It is forever ancient and new.

Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih is an award-winning Khasi poet and writer. His latest works are The Distaste of the Earth (Penguin), the critically acclaimed Funeral Nights (Westland), The Yearning of Seeds: Poems (HarperCollins) and Time’s Barter: Haiku and Senryu (HarperCollins). He is the co-editor of Late-Blooming Cherries: Haiku Poetry from India (HarperCollins) and Dancing Earth: An Anthology of Poetry from Northeast India (Penguin).

Kabir Deb is the interview editor of Usawa Literary Review.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates