Reviewer: Aditi Yadav

(Instragram: i_galacticus)

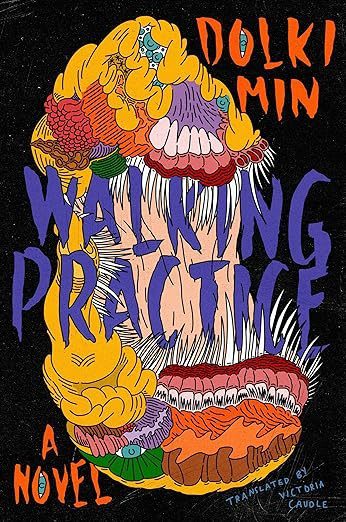

Title: Walking Practice

Author: Dolki Min

Genre: Fiction/Novel

Language: Korean (Translated into English by Victoria Caudle).

Year: 2023

Publisher: Harper Via.

Pages: 176

Price: INR 306/-

ISBN: 978-0063258617

Would you consider yourself a female, or a male or both or neither or somewhere in between, if society had no gender specific labels, roles and expectations? Is gender a problem of biology or socialization, nature or nurture? And how would a species from outer space make sense of it all to blend in?

South Korean author Dolki Min’s debut novel explores homo sapiens and their life on earth, with alien eyes, violent mannerisms, uncensored speech and raunchy humor. The book originally was self-published in Korean by Dolki Min, who also designed the other-worldly intriguing book cover. Even in real life, the author themselves have not made their true identity public, making them as mysterious as the protagonist.

The novel defies conventional classification of genre, just like how it questions gender stereotypes. It is a potpourri of satire, sci-fi, noir, and several earthly and unearthly concepts. It takes you on a ride into ‘otherness’ where explicitness is artfully served with dark comedy. It is loud, brash, often gross with unfiltered emotions, challenging creative limits and institutionalized concepts inside human minds conditioned and reinforced by socialization.

The protagonist Mumu is an alien, one of its own kind lonesome creature on earth. They crash-landed about 15 years ago as a space traveler whose home planet had been destroyed. Since then, they have been striving their best to adapt to the ways of earthlings and pretend to be human. But their onerous efforts come at the cost of human lives. The reader gets to know this secret in gruesome and explicit details as the protagonist narrates their daily life. Mumu uses dating apps to find potential candidates for hooking up. Once they satiate their corporeal pleasures, they mercilessly devour these people. That’s how they derive energy to maintain their human form and vitality. They reside in a house in which is deep inside the woods, and only drag themselves out for food.

Mumu initially teases the reader, giving a lot of details but saying nothing about their gender. The truth however is that they keeping changing the gender based on the person they hook up with. We see Mumu transform into both male and female forms, yet being discontent about a lot of things like love and life.

They want to be loved, an emotion perhaps they picked during their stay on earth. Mumu has several lovers, whom they did not kill to satisfy their hunger, instead allowing them to live because of Mumu’s romantic interest in them. But Mumu’s experience in gender transformations offers great insight on gender and its discontents. “Acting as a woman is far more intricate than acting as a man”, they observe.

They explain this “bullshit” saying, “When you want to be a woman, follow my advice. Speak in a thin, pretty voice. It has to be high-pitched. … Cover your mouth when you laugh. … Show enthusiasm about grocery shopping and cooking. Beef up your cooking skills. Be unfailingly kind to others—especially men… Make sure you attain a slim figure and maintain it for your whole life. Play dumb, with no regard for your actual intelligence. Disparage your driving. Be chatty. Try your best to sincerely enjoy cleaning and doing laundry. Think of weakness as a virtue, and let your strength rot away. Wear makeup even in your dreams. Wear bright clothing. Conceal your sexual appetite, and take it to your grave. Become shyness incarnate. . . . .. Men should do the opposite. Just don’t act like a woman.”

The title, Walking Practice, itself is an allusion to the discontent and discomfort Mumu faces on earth. On their original planet, they could easily walk on four legs, or three legs with an arm. But it is an ordeal to keep up with bipedal form on earth. Despite 15 years on this planet, they haven’t got accustomed to walking. The simple act of walking has also been cleverly used by the author to reflect on gender discrimination, “Men can walk however they like, but a woman must walk like a woman. “However they like” means walking with their legs splayed and their shoulders shaking, Mumu reflects,

“when I was first learning to walk like a human, I couldn’t, for the life of me, figure out the difference between men and women. In my eyes, all humans looked exactly the same….But humans keep bringing up their criteria and judge me by it. . . their expressions and words that question my humanity irrespective of where I am made me tear myself apart and rebuild myself piece by piece. … I made myself complicit in humanity’s scam and adapted myself to the local ecosystem. That being said, I still don’t feel an intimate sense of belonging, but at least I don’t starve.”

Mumu sounds very relatable reminding us of the numerous occasions, we felt alien within our own skin, stranger to our own identity, despite being surrounded by fellow homo sapiens. The vision and voice of the alien protagonist hits the reader’s subconscious to dig out the discontents one faces on account of gender discrimination and questions the gender polarization institutionalized by human society. Sometimes Mumu sound like a wise stoic philosopher, brooding on human condition and chastising all they find ridiculous. Though they are a serial murderer in literal sense, you may still end up sympathizing with them. After all it is the only way they ‘survive’ here- quite like how humans put up with a lot of stuff against their will, only to stay alive.

The work has been lucidly translated from the Korean into English by Victoria Caudle. The nuances of articulation in Korean are creatively treated in the English translation with experimental text setting. Inter-alia discussing these challenges, Caudle pertinently pens in the translator’s note, “Translating this novel at a time when queer activists in Korea are fighting for an anti-discrimination bill and when the rights of queer Americans are under sustained attack reinforces my goal as a translator to make queer narratives visible and visceral…Walking Practice is a novel that yearns for community as much as it is a novel that plays with notions of gender and sexual expression.”

Walking Practice feels both human and alien, stifling and liberating, while at the same time, reminding humans to practice free living, beyond the constraints of gender and identity instead of ceaselessly living and dying in discontent.

You can purchase the book here.

Aditi Yadav is a public servant from India. She is also a South Asia Speaks fellow (2023). Her works appear in Rain Taxi Review , EKL Review, Usawa Literary Review, Gulmohur Quarterly, Narrow Road Journal, Borderless Journal and the Remnant Archive.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates