At ten years you knew. Yet you did not. About sparrows and men and women and babies. About eggs and flesh that you never tasted. And of feathers as soft as cotton.

The room faced a hedge through which you could make out the house next door. Built on a slope, it was a longish building with half the first floor supported by cemented pillars. The ground floor began where the slope flattened out but on the slope itself, sandy and dark, were chicken coops and wooden crates that contained fist-sized rocks.

The first floor was rented out to the Institute of Geological Studies. During week days the office remained busy. But twice a year the men went off on expeditions. Then, the office was temporarily closed. Out in the front yard were parked Jeeps and trailers and where the drivers sat on a grassy slope and whiled away the hours. On the steps that ran parallel to the hedge, and leading to the rooms downstairs, the moss had grown thick, with sunlight caressing the area for less than an hour before the crows flew home.

For many years, Nanda Laal, the caretaker, and, later, along with his wife, Mayalina, looked after the premises. They stayed in the ground floor comprising a drawing room, two bedrooms and a kitchen. It was only many years later and after her husband passed away and the children had migrated abroad that old Mrs Rahman, who owned the property, came to stay with them. Because the hedge sloped down sharply to the east, I had a clear view of the entrance to the ground floor from my room.

Three plum trees that grew inside our compound spread their branches over the hedge, forming a porch of sorts and sometimes I would climb one and peep into the drawing room through the ventilators. There were also days when I made my way through a bolt hole in the hedge and crawl into that sandy slope underneath the first-floor boards and search for dismantled, empty wooden crates. Once in a while, a hen or two, soon-to-be mothers, would warn me off but otherwise the space was free for my ventures.

Between the sandy slope and the drawing room was the kitchen, with a single window facing the plum trees. Whenever I crawled into that darkish cavern the fragrance of cooked food came floating in. But over and above this was the smell of chicken feathers and poop and straw, of rocks as old as the moon, of dry pinewood and rusty iron nails and of sand that had not felt sunlight for half a century and more.

I liked Nanda Laal. Dark, thin and tallish he was a shy, nervous man with an occasional smile as brief as a firefly’s glow, his thick hair plastered to his scalp with oil. The wrinkles on his forehead never left him, displaying a kind of perplexity verging on innocence. I did not think of him in this manner, then: it was only after many years had passed.

I was two months into my tenth year when I first saw Nanda Laal picking up the dead body and the gooey stuff from the drain outside my room. It was late November, the cold keeping us in our beds till the sun was well over the trees. Once in a while, on days when we knew that the dew would turn to ice during the night, I mixed water and apricot juice in a saucer and placed it on the roof-top. Early in the morning, the next day, and before the sun came up, I would climb the wooden ladder and bring down the plate, my own home-made candy.

It was biting cold that morning as I put on my woolen socks when, through the window, I saw Nanda Laal in a thick brown sweater and a pair of blue-and-white striped pajamas crawling into our compound through the bolt hole in the hedge. It was that period when night still fought desperately against the breaking of day. I pressed my face against the window pane, my heart thudding for no other reason that I could think of except that I had never seen Nanda Laal looking so ghost-like.

He crawled forward, an aluminum spoon in one hand and a container in the other and then crossing the dry grassy portion between the hedge and our house, eased himself over the drain alongside my room and with the spoon scooped out a feathered but skeletal body encased in cracked, greyish shells. Along with it dripped the yellowish-white and slightly thick liquid that had oozed out into the drain. I stood on my toes, watching him filling up the container, a bowl no bigger than my palm and then in less than sixty seconds he had gone back through the hole to his compound.

I waited for a few more minutes, watching him enter his house and then I went out through the veranda at the back and down into the yard. It was as cold as it could get but as I bent down over the drain a sparrow flew out from under the eaves. It chirped frantically and then darted into the hedge. On the drain’s floor were remnant lines. The spoon had scraped out the feathers and bones and the yolk and the white. I sucked in my breath, taking in the smell that a new day brings but from the drain itself there was no smell.

All along the length of the roof and between the rafters the sparrows had built their nests. They had always been there. Sometimes, especially during winter, I would come across an egg or two, bluish, speckled, round marbles with the gooey, semi-transparent liquid oozing out and caking the drain. Once or twice, a limp, skeletal, featherless creature, perhaps half the size of my little finger, the legs as delicate and skinny as baby earthworms lay between the broken shells. Eyes closed, the wings, if at all they could be called wings, scrawny. Lifeless.

I had placed the ladder up against the roof the day before and now I climbed and carried down the plate but my mind was on Nanda Laal and the way he had gone about collecting what he did. I entered the house, placed the plate on the dining table, my hands numb from the cold. A cock crowed. Against the windowpanes the light began changing. As I climbed into bed once again, I thought I would later ask Sobin why it was that Nanda Laal wanted the broken eggs.

At sixteen years, Sobin, the water-carrier smoked cigarettes without the smoke coming out from either his mouth or his nostrils. Whenever we played badminton, he tied his shoulder- length hair with a blue bandana around his forehead. Carrying the water-buckets slung from coir ropes at either end of a bamboo bar across his shoulders, he would swagger into our compound, his eyes aglow with a kind of excitement that I thought only champions possessed. He had taught me how to whistle when none in my class could and how to roast potatoes over hot coals down by the cow shed. And sometimes, hanging around with me after his chores were over, he would whip out his catapult, aim quickly and bring down large yellow grapefruit, rabab tenga, that grew in plenty in the garden. I thought there was none more heroic than him.

But Sobin had taken the day off and by next day I forgot about the incident.

A week went by. It was past ten in the morning and I was in my room, trying out sketches in the drawing book when a rooster’s long-drawn crowing followed by the clanging of utensils in the kitchen distracted me enough to look out through the window. High above, over our neighbour’s house, a red paper kite with a long tail spiraled crazily and then in a sudden swoop fell on the roof, sliding down the slant facing our house. For long seconds it hung low over the wall, and then swaying seductively it disappeared between the concrete pillars supporting the first floor.

For a split second, I hesitated. Then, throwing caution to the winds, I ran out through the back door and bolted through the hole in the hedge. The steps were deserted. Sprinting across, I crawled under the floorboards, the soft sandy dry soil on my palms and knees. The kite had come to a rest against a pillar close to the kitchen. A lost kite, I said to myself. Finders’ keepers. And snapped the string. I was about to retreat, when, from the kitchen, came voices. Still crouching, I went up close to the wall.

Because I had been keen on the chase it was only now that I thought of the smell wafting around. It was a familiar Sunday smell, a middle-class, or a working class, family smell, a smell reflecting thrift and togetherness and of birds and animals cooked for satiating human taste buds. Mutton curry, I thought. But today was a Tuesday, and, besides, it wasn’t noon yet.

“It tastes better than last time,” said Nanda Laal, his voice deep and throaty. The smell was rich, spicy, warm, soft and cuddly. Despite the situation, I felt saliva on my lips. Then, “You paid him the amount?”

A moment’s silence. “Yes,” said Mayalina. “But I think he wants more.”

From the road came the sound of a car’s horn. A crow cawed. I waited. But the voices in the kitchen had stopped. Kite in hand, I ran up the steps and through the hole and back into my room. The whole thing had taken less than three minutes. It was a few days later when through the hedge I saw Sobin walking down the steps and knocking on Nanda Laal’s door. In one hand was a bag made from a tyre. I had seen our local cobbler making one. You pasted and stitched one end of a black rubber tube so that whatever you carried did not leak and then you stitched a long leather strip at two ends against the open end. It could well have been a school bag. But all that the bags were thought worthy of were for carrying leftovers from the kitchen to the municipal garbage dump or for packing carpenters’ or cobblers’ tools or filling it with bran and rice and then slinging it around a horse’s neck.

I watched Sobin through the windows. His long black hair glistened in the afternoon sunshine. The green from the hedge had long since gone and now only the dry brown leaves remained, clinging to the scrawny branches like nameless, faceless orphans. A soft December wind fell on the curtains. Outside, high up against the sky, kites and perhaps an eagle or two, flew in lazy circles. The door opened. Mayalina, plump of face, pink and fair, her eyes shining bright, smiled at him. I had not seen her for several months. Unlike Nanda Laal, she rarely ventured out of the house. Even when she did, they would take the back door and then up the grassy path, out of my view, to the road. But now she looked fat, her tummy sticking out, round, under her white-and-yellow gown.

A baby, I thought, she is with child.

Sobin said something. Then he eased the bag down from his shoulder. I saw the rupee notes in her hand as he quickly took them while, with the other hand, she picked up the bag as easily as if she were picking up a towel. Less than a minute later she returned and handed back the bag. As Sobin climbed the steps, a flock of sparrows suddenly flew over the doorway. And then, chirping shrilly, sped up the walls and to the eaves. I did not pay much attention to them. They were always around. But as Mayalina closed the door I glimpsed a piece of brown cloth, or, what, in all likelihood could have been brown cloth, fluttering on the floor.

The next day, early in the morning, cousin Pona arrived from Sivasagar. He was a loud- mouthed boy two years older than me. I spent the next five days tolerating him as he strutted around, boasting about his escapades in his boarding school in Rajasthan. I had forgotten about the black rubber bag, forgotten about the sparrows in the drain, about Nanda Laal and Mayalina.

When he finally left on the sixth day, I went down after lunch to the haystack built adjacent to the cow shed. Pressing my back against a bale, and then snuggling in deeper, feeling the warmth from the sun in the hay caressing me, the cows now silent after Bahadur had fed them before leaving for the market. I must have dozed off for a while but when next I opened my eyes the sun had gone behind a long cloud. I turned around, wondering if the hens under the shed had laid any more eggs, when I saw Sobin climbing the shed’s roof.

There was no ladder nearby and I was sure he must have hauled himself up, using a beam under the roof. He was lean and tough and agile and now he was lying flat on his stomach, wriggling along the rusty corrugated iron sheets. Because I was tucked into the stack, he couldn’t see me. I watched him now, my mind still dulled by the warmth from the hay as, slowly, like a blind man feeling his way he lowered his head over the edge and groping with his fingers under the eaves brought out a bunch of twigs and leaves and feathers from under a rafter. The shed, too, like our house, was full of nests. But there were no sparrows around now. Perhaps they had fled when he had climbed the roof.

Using both hands, he removed the feathers, one after the other, shoving them into the black rubber bag and just as carefully replaced the twigs and the leaves into the clefts between the rafters. It was that time in the afternoon when the wind goes still. But my heart had begun beating faster and louder than the school drum. There was no reason why I couldn’t have simply called out to him but it was also one of those moments when you knew that something was not quite right.

High above me, an eagle circled lazily. I tried focusing but, as if hypnotized, my eyes swerved towards Sobin. He had shifted position, his hands filled with another bunch, once again separating the feathers from the rest, pushing them into the bag and then tucking the twigs and the leaves back to where he had first taken them out. Thrice more he did this and then he drew back and crouched, his back arched and outlined against the sky. Half-facing the haystack, he lowered himself down the roof and then he was out of my vision.

I lay as still as I could despite my heart beating wildly. It was almost as if I had taken part in the operation. Worried now that he might round over to where I was, I dug myself in deeper. And then I heard his footsteps on the wooden planks that lay on the dirt path leading to the shed. A cow urinated, the sound loud in the otherwise quiet afternoon air. A ripened squash fell from a vine high up in a tree. I watched it roll down the slope, waited for a second more and then poked my head out. Sobin was climbing up the slope towards my room. In his hand was the black rubber bag. And then he was through that bolt hole and into the other compound.

By the time I reached home he was gone. I did not know what to do. To tell someone what I had seen would not amount to much. There wasn’t anything serious that he had done, not that I could think of. After all, he had re-arranged the nests. Yet, even at ten years of age you could sense that something was afoot. Sleep came late to me that night and the last thought I had was whether the sparrows were warm enough in the wintry cold.

Early the next morning, a Saturday, we went to our school for my text books for the next session. At nine forty-five, father got down at his office while Ma and I returned home. For well over an hour both of us fussed over the books, the labels and the brown covers. At eleven-thirty, I heard Sobin pouring water into the three drums in the open yard next to the kitchen. It was close to noon when Ma entered the kitchen to prepare lunch. I stacked the books on my table, inhaling the smell that only fresh books and paper can bring and then I went down the long uneven slope to the cowshed where I knew Sobin would be filling the troughs with water meant for the cows.

I knew he would not expect me for it was only after lunch that we sometimes came down to pluck pears and squash. But as I came up behind him, close to the shed, the smell from the dung, raw and sharp, suffusing me, I saw him aiming his catapult, drawing back the rubber strips and then letting loose the sun-hardened clay marble. The next second, from guava tree fifty feet away, a bird dropped. Like a stone. Sobin sprinted forward.

I saw the bird then, a sparrow, the neck twisted upwards, the once perky feathers now limp and lifeless, like a piece of rag in a butcher’s stall. Light- black dots peppered the wings, the feet tiny. Placing the catapult on the ground beside him, half-squatting, he quickly picked up the bird, easing down his chest the black rubber bag that hung from his shoulder.

Almost without thinking I lunged forward, grabbed the catapult, turned around, and ran. I ran as fast as I could, a fury that I had never felt before blazing from my very guts. He was a murderer. Of a creature as innocent and small and helpless as a sparrow.

I was halfway up to the house when I stumbled over a small heap of logs covered by pumpkin leaves and straw. He came up fast, caught hold of my shoulders, swinging me around, pulling the catapult out of my hands. Panting heavily, one hand clutching my shirt collar, his eyes wide and round and angry, he glared at me. I glared back. I knew he wouldn’t hit me. To have done that would have earned father’s wrath.

He withdrew his hands. I wanted to say something but my throat had gone dry. The black rubber bag slung across his chest looked blacker than ever before. It was not the blackness of colour. It was the blackness given to souls that do not know mercy, a blackness that thrived on death, like a sky forever without lights, without life. Even at that moment when I thought I would break into tears, I thought, just how many had he killed?

“Why?” I said, my voice so hoarse I thought it wasn’t mine.

Muttering something under his breath he went up to the shed. From a peg in the door, he brought down his faded, patched, grey gabardine jacket. The long hair swayed unevenly on his shoulders. A cow mooed. The sun slid above the tall eucalyptus trees near the shed. A cold wind swept down the slope.

Hurriedly, perhaps fearfully, he put on the jacket. And then, his voice rough, unrepentant, he said, “They wanted feathers. Sparrows. A pillow for their baby.” Turning around suddenly, he loped up the slope and out of the compound. I knew he wouldn’t come to our house again. But I didn’t care. He was not only a murderer: he had also sought money to do the murdering.

I sat down on a half-rotten eucalyptus trunk, the bile rising in my throat from the anger that had possessed me. From behind me, from the cowshed came the chirping of sparrows. They were quick, sharp, shrill sounds but, somehow, I thought of music from a piano.

Like a tired old man, I got up and went to the spot where Sobin had dropped the bird. It was still warm to my touch. I traced the curve that was its chest, soft and feathery, the whitish- yellow beak slightly ajar, as if it was trying to suck in air, the eyes as helpless as a new born baby’s, the eyelids now resting halfway over the cornea; the tail, spruce and straight and half as long as the rest of the body. The legs had gone stiff, the tiny claws curled and shriveled. And from that impossibly beautiful neck dripped blood.

Ten feet away, the ground had been dug for fresh planting. I picked up a twig, dry and hard and pointed and dug a hole four times the length of my thumb. When the burying was done, I went over to the haystack, picked up a handful of straw, came back and placed it over the grave. It was hardly a proper marker but it was the best I could do, a nest for my sparrow.

There was still an hour more to lunch. I washed my hands in the yard and went back to my room. The house on the other side stood silent, empty of life. But from the hedge came chirps. I never told anyone about the sparrow down in the garden. My telling would not bring it alive. Even at ten years I knew that words are meant only for the living.

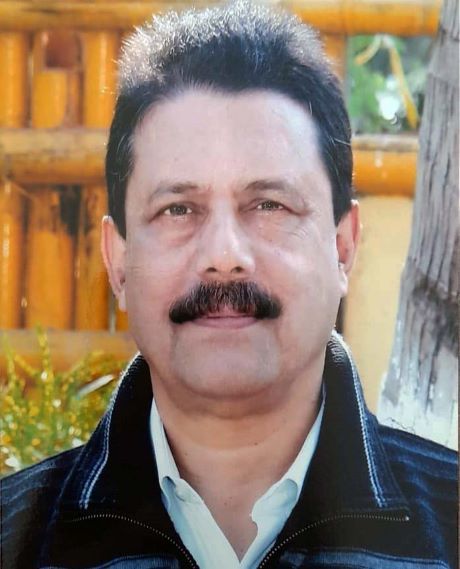

Dhruba Hazarika is a novelist, short story writer and a columnist. He has written two novels till date, A Bowstring Winter (2006) and Sons of Brahma (2014), and a short story collection, Luck (2009). During the last thirty-five years, he has contributed as a columnist to The Sentinel, The Telegraph and The Assam Tribune. His short stories have featured in several magazines, including Indian Literature, New Frontiers, Melange and The Bombay Literary Magazine. A recipient of the Katha Award for Fiction in English, his works have been included in the academic syllabi of several universities. A former civil servant, he divides his time between Guwahati and Shillong.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates