In another corner, a short video (at first glance) seems to contradict Chhachhi’s visual imagery; titled Gaali Geet, an intimate group of Dalit women sing raw songs of desire, longing, and pleasure. Their gathering evokes a shared moment of respite, perhaps, and was formerly a pre-wedding ritual passed down generations within the community. Captured by artist Ranjeeta Kumari, this oral tradition shifts our stereotypical presuppositions of a radical woman; here, they claim agency against structural patriarchy not through protest, but rather with whimsical, spirited, and playful gestures of song and collective belonging. For Kumari, the poetics of violence need not be overt agitation or representation, but often take more complex and nuanced forms within our social relations.

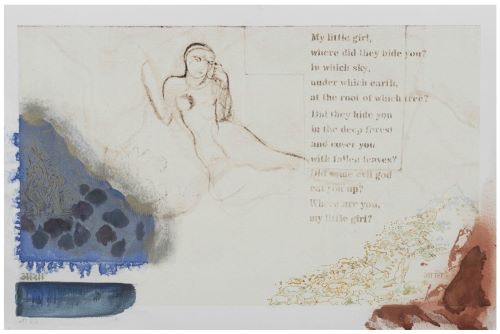

At each step of Adajania’s curation, you encounter an unsettling question: what does it mean to aestheticise violence? Or rather, how does one grasp this cryptic relation between art and politics, specifically amidst an onslaught of structural violence against women? Whereas the exhibition begins as an archive – thus with the goal to document or ‘represent’ historical violence – interestingly, some artworks move beyond the empirical (and phenomenological) to explore the emotional, the interiority of our psyche. For instance, Nilima Sheikh returns to ‘When Champa Grew Up’, her series of paintings from 1984 that traced the life of Champa, her muse, from childhood to a young adulthood, and inevitably halt with her death by burning in the hands of her in-laws. Sheikh revisits this narrative thread with darker contours; her new paintings emerge from the undead of their former selves, delicately rendered with rust and blood-red stains. Here, the fiery memorial holds not only Champa’s voice, but remains haunted by all others that succumb to her tragic fate, as Sheikh inscribes their immortal names – from Kathua to Hathras to Jammu – on her last painting, wherein a horde of agitated bystanders gather around the tenuous, lifeless, and silent body of young child.

On the other hand, at times, language itself—visual or textual—becomes inadequate to grasp the interiority of a wound; as Emily Dickinson once wrote poignantly in her poem: “Pain — has an Element of Blank”. This absence of an adequate signifier forms the crux of Mithu Sen’s approach; here, the artist resides at a government supported orphanage for girls in Kakkanad, Kerala. During her stay there, Sen transforms into the fictional character of Mago, an alien with no language, who speaks rhythmic gibberish to converse with the girls, and each of their absurd yet intimate interactions is captured on a camera shared by all the residents. Sen edits this footage to protect the identity of those girls, and the final video installation on display – titled ‘I have only one language; it is not mine’ – emerges as a film devoid of immediate signification or meaning.

Image sequences appear as red outlines, quietly evoking the landscape of “bloodlines in search of a body.” [1] In a conceptual vein, Adajania asks: “How does an alien with no language converse with girls who have been emotionally and sexually abused? By forsaking language as she speaks to the forsaken, Mithu Sen could be pointing to its colonising powers, which bleach reality of its heterogeneity.” [2] Moreover, in this work, Sen sheds all positivist desire – she doesn’t attempt to compose an ethnographic documentary wherein outsiders may glimpse into the agonising world of her girls in order to form a cathartic narrative with a neat resolution. Instead, one encounters playful and shifting fragments of translation, haunting memories in recoil, and the flaws – or voids – built into the very mechanisms that sustain language.

In contrast, Sosa Joseph approaches violence with the sensitivity of a storyteller: she doesn’t seek to represent or archive a traumatic history, nor does she romanticise the resilience of a victim or survivor. Here, our contradictory world – an eerie horror woven into the ordinary – emerges in luminous contours, striking both terror and wonder with a single note. In Joseph’s ominous painting, a wounded, distorted woman not only subverts the patriarchal gaze – but more importantly, she glares back, severely and unswervingly, into the very eye of her oppressor. Titled ‘Pieta’, her work refers to a popular visual trope: Mary holding the lifeless body of Jesus Christ, rendered with profound sorrow and tenderness, often evoking affects of pity or compassion. Joseph juxtaposes this symbolic imagery with the story of Bhoopathy, an Adivasi woman, whose son, Abhimanyu, a Left-wing student leader, was assassinated on campus by extremist forces in 2018. But Joseph’s protagonist doesn’t ask for your pity nor does she appeal for our empathy. As she holds her martyred son, Mary is enraged and her manic grief resounds with force, reverberating through the canvas. She demands absolute retribution in the present – no more or less – as her voice echoes upon the distant horizon yet to arrive, but if you look closer, a soft hint of dawn encircles this desolate field.

[1] As cited by Nancy Adajania in her curatorial note, JNAF Gallery, 2022.Sonali Bhagchandani is a writer and curator based in Mumbai, India. She obtained an MA in History from Goldsmiths, University of London (2021) and a BA in English Literature from St. Xavier’s College (2016). Her research explores the intersections of narrative strategy, emotion, and memory through the material history that consolidates ‘postcolonial’ India.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates