By Sanjena Sathian

Upon my arrival at Lia and Gor’s, I’d apologized for being a bitch about Tadpole, and Lia had adopted that sympathetic affect again, lowering her voice. “This must be hard for you,” she said. For a moment I wondered if she’d guessed about the abortion, and relief cooled me, but then she said, “You still have time.” “For?”

We were making up the double bed in the future nursery. Lia tossed me a pillow and a pillowcase. “All this stuff.” She jerked her head as if to say, A house, a home. I remembered, suddenly, helping her move into her first New York home: a closet-size bedroom in a Greenpoint apartment shared with two Craigslisters. We had scrubbed the place for hours to rid it of an ominous chemical scent, and when it still reeked ages later, Lia had collapsed on the floor, half laughing, half crying, and rubbed her snotty face on my shirt and admitted that she was terrified—what if she did not figure out how to be a real person, out here?—and I had touched her hair and promised that I, too, felt like a cipher to myself.

“Kids, if you want them,” she said now. “A partner, if you want one. You’re just in a shitty life season.”

I nodded, shoving the pillow into the silk fabric and zipping it shut.

“Any word? From Killian?”

“No. I’ve been trying to track him down. Well, sort of.”

She frowned, her attorney brain switching on. “Let us know when you need a lawyer.”

“I don’t have any money, Lia,” I said, which was true. My income from editing college application essays was dwindling, and when my grad school stipend restarted in August, it would barely cover daily expenses.

Lia flushed. She had become one of those rich people who found it gauche to discuss finances.

“He can’t ghost you forever,” she said. “Are you seeing anyone new?”

“Not really.” Max was gone for good. He’d texted once to make sure I’d gotten to Brooklyn, and then when I replied saying I didn’t want to see him anymore, he sent a too-quick response, agreeing with my decision.

“Do you want any of this?” Lia asked, kneeling to tuck in the fitted sheet. I dropped to meet her and pulled my side. It stretched like one of those life nets used to catch suicidal jumpers. “Do you want to be married again? Have a family?”

I almost replied with my old line: I don’t know, or Not yet.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “But not wanting it is its own kind of … hard.”

“I guess I can see that,” she said, pulling a strained expression that suggested she could not. “You know, Gor and I are, sociologically speaking, the exception. Our generation is having fewer babies than ever. It was in the Times this week. People can’t afford to buy homes, so there’s nowhere to put their families. Statistically, you’re the majority.”

“Lia, you bought a house.”

“We bought a condo,” she said, with a dignified sniff.

She beckoned me to follow her to the kitchen. Sandra Day O’Connor appeared out of nowhere and bit me on the toe. “Oh, she’s just love-nipping,” Lia said. “Anyway, you’re a grad student. Don’t you know a whole bunch of child-free types? Gays and stuff?”

We’d had this conversation before. Find your people, Lia loved to say, which always stung, as I’d sort of thought she was my people. In college, she’d once asked if I was sure I wasn’t a little bit gay, because the LGBT groups might take me, and if not them, then maybe the South Asian Student Association?

Now Lia continued, “Or is this, like, an Indian identity thing?” Her voice lowered to a respectful hush on the word Indian.

“I think it’s an identity thing,” I said, thinking of Dharma and her desire to believe that my shit was all attributable to immigrants. That what I was feeling had nothing to do with her.

Lia’s head was buried in the fridge. There were at least ten more sonograms of Tadpole on the stainless steel. “I’m fucking starving. It’s like my body’s trying to make up for the first couple of months. I couldn’t eat anything salty. I never knew salt had been, like, the great joy of my life. It’s all so weird.”

Sandra Day O’Connor leapt onto the countertop. Lia chided her.

I took a deep breath. “I’ve been meaning to tell you … I’ve been getting some weird shit from strangers these days.” I had waffled on how much to tell Lia about the texts, initially figuring I’d say nothing because explaining the roots of the mix-up would require me to tell her about my abortion, and I assumed it was in bad taste to discuss abortion with a pregnant woman.

But matters had grown more bizarre by the day. Everyone who’d contacted me—the unknown texters, Shazia, Miranda—had since vanished into the ether. There was a record of the messages and calls, which was the only thing that led me to believe I was not insane. At night I opened the photo taken in Bombay and stared at it furiously, as though the woman in the picture would suddenly move, turn over her shoulder, wink at me, finally, revealing some secret.

Then, the night I arrived at Lia’s, I checked my phone to find that I’d been added to a WhatsApp group without my consent called Bandra Expat Moms. I scrolled the list of members—hundreds. It was not the first time I’d been dropped into a WhatsApp group that then flooded my notifications all day; that was daily life in Bombay. I wrote to the whole group: how did you people get my number?? and someone said I was free to leave whenever I wanted, but please see the group’s guidelines for conduct: rudeness was not tolerated. Then someone else replied suggesting they institute a zero tolerance policy for meanness because otherwise what example were they setting for their children? and someone else said to be kind above all! because the whole point was that they were all going through something together and hadn’t they been snapping at partners and electricians and maids on occasion, due to stress? and someone else said to please call maids domestic workers and asked by the way what the charge was for a night nurse in Bombay because her friends in London swore by them but she found the idea a little old-fashioned but also it was India and wasn’t it good to provide employment opportunities? I’d planned to lurk on in the group, to see what happened next, but after twenty-four hours I was kicked out. The last message I could see was an opinion poll on the zero tolerance policy. The future moms had elected in favor, voting me off the island.

It was all so strange that I had actually booked an appointment at a free clinic during my first week at Lia’s to have the position of my new IUD checked. When they’d told me it was fine, I had whispered to the physician’s assistant: You’re sure I’m not pregnant? It was as though the past were overlaying the present. All these texts seemed to be emerging from some other realm, a parallel universe in which I had not left Killian on that beach in Goa, in which I had not had the thing sucked out of me, and when I was very high I had the thought that perhaps the other timeline had grown hungry, hungry like an evolving fetus, and decided it was time to devour the life I’d tried to make on my own terms. I did not say any of this to the PA, but she must have spotted the glimmer of crazy in my pupils, because her tone changed, and she spoke to me as though I were extremely stupid and perhaps unstable. I was not pregnant, she explained. Hardly anyone got pregnant with an IUD. I begged for proof. I could feel it in me, I said. I hadn’t noticed fast enough last time, but I knew now. Don’t they say a mother knows? The PA showed me, clearly, the arms of the implant, extended into a superhero T, then asked if I needed a referral for a therapist.

I was still deciding whether, and how, to share some of this with Lia when I heard the sound of Gor’s keys in the lock.

“Babe,” he called. “Did you order dinner?”

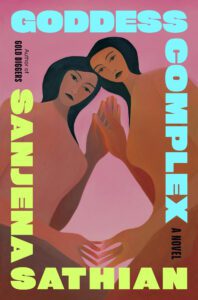

Excerpted with permission from Goddess Complex by Sanjena Sathian published by Harper Collins India 2025

Sanjena Sathian is the author of the critically acclaimed novels GODDESS COMPLEX and GOLD DIGGERS. Goddess Complex, released in March of 2025, was named a top anticipated book of the year by TIME and has been named a New York Times Editor’s Choice. Gold Diggers was named a Top 10 Best Book of 2021 by the Washington Post and longlisted for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. It won the Townsend Prize for Fiction.

Sanjena’s short fiction appears in The Best American Short Stories, The Atlantic, Conjunctions, One Story, and more. She’s written nonfiction for The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Drift, The Yale Review, and NewYorker.com, among other outlets. She also writes for screen.

She’s an alumna of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has taught fiction at Emory University, Mercer University, the University of Iowa, and Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. She lives in Hong Kong and will teach at the University of Hong Kong in spring 2026.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates

Join our newsletter to receive updates