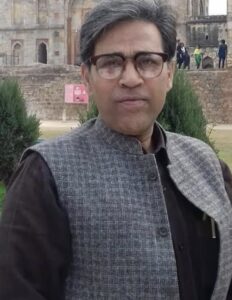

In Conversation with A. Naseeb Khan on The Book of Death

Image Courtesy of Westland Books

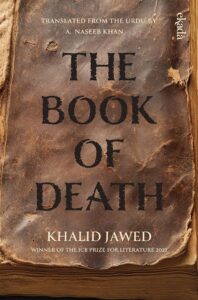

Rituparna Mukherjee : Hello Naseeb Ji! Thank you for talking to Usawa about your latest translation of Khalid Jawed’s The Book of Death. Interestingly, the main text that is the diary of the protagonist appears as a translated text itself in the novel. What does that mean for you as a translator?

Naseeb Khan : Hello Rituparna Sahaba! Thank you so much. Deep gratitude to Usawa. Yes, the ‘original’ text, as the author himself tells, presents itself as a translation within the story. The author immerses us in a world where language itself is a site of meditation and distance. By presenting his text as the translation, he proposes that pure voice is perhaps impossible to hear, thus what reaches us is refracted through another consciousness. This deliberate blurring of original and translation creates a resonant space where voice is in perpetual transit. But the pre-existing condition of the text does not diminish the translator’s role. It redefines it from a mere transcriber to an essential co-creator of meaning. As a translator, I entered this linguistic space, reclaiming a voice that has been journeying through loss, mediation and time. My task, as a translator, was reanimation, to give breath to a voice that had already crossed one threshold of silence, and must now cross another.

RM: The preface of this novel hints at the erasure of an entire civilization due to an ecological crisis. In a world that is already reeling under one ecological crisis after another, how important do you think translating literary works is for the sustenance of civilization?

ANK: The novel’s foundational vision of a world undone by ecological crisis, and the looming erasure of entire civilisation, imparts the translator’s task a profound and urgent dimension. In this light, the translation ceases to be a mere technical exercise, it becomes an act of ethical preservation. As landscapes are erased, species disappear, languages fall silent and a civilisation’s memory frays, stories endure as the last seeds of a vanishing world’s consciousness. To translate, then, is to become a gardener of memory, planting these seeds in the new soil of another language. This act cultivates remembrance, fosters exchange across the ruin of loss and inspires empathy necessary to sustain the ecology of the human spirit. Thus, every translation is a defiance of oblivion, a pact with the lost, ensuring that that their dreams and warnings are not buried with them. The translator becomes a keeper of the dialogue between existence and memory, a medium ensuring that voices from beneath the rubble still murmur, then speak clearly and finally resonate across time and borders.

RM: The novel is slim, but very heavy reading. How did you manage to manage to retain the atmosphere of paranoia and chronic depression that the protagonist constantly negotiates?

ANK: Yes, that’s precisely the central challenge. The novel’s substance lies not in length but in its intangible mood and atmosphere – a pervasive dread and a deep, lingering melancholy. My approach was therefore less about translating words than translating a psychological state, a climate of paranoia and a chronic, low-frequency despair. I considered the text as a fragile artefact, not of events, but of a consciousness in disintegration. Fidelity required resisting the instinct to explain ambiguities and complexities. The author’s dedication of the novel to the Sanskrit vowel ऋ is no ornament. Its inward-turning, pressure-bearing curves become the novel’s method, currents that falter and resume, strands that knot and hold. Structure, feeling and thought bind together, the formal tension shadowing emotional knots and existential entanglement. The plot is not linear, it is labyrinthine, like the letter ऋ itself. To be truthful, I read the text aloud to internalise its unsettling cadence, the halting rhythm and precarious shifts between observation and delirium so that I could echo that disorientation and emotional vibration in English. I wished to transport the protagonist’s very being, to preserve in English the palpable weight of the story’s silences and the suffocating pressure of its air, so that a new reader not only reads about but feels the inner world.

RM: Urdu as we know is a language with a cadence and a beauty of its own. How did you manage to convey the beauty of the several aphorisms in this novel or most importantly, the recurring images of existential disgust and rot that the author uses liberally?

ANK: That’s a very perceptive question. Urdu, with its intrinsic musicality and layered imagery, can hold elegance and corrosion within a single phrase. The novel works through this duality, its aphorisms gleam like polished fragments of wisdom, yet they are unearthed from a world in active decomposition. My task as a translator was to let this contradiction breathe in English. I resisted the urge to domesticate the text, allowing an echo of Urdu’s cadence, its inward melancholy and ironic grace, to permeate the sentences. The aphorisms, especially, required restraint, too literal, and their resonance flattens, too embellished, and their stark truth recedes. As for the recurring imagery of rot and existential disgust, I considered it not as ugliness to be softened but as essential texture, the very fabric of a civilisation’s body breaking down. The beauty here is not separate from the decay; it arises from it. Thus, the translation became an effort to preserve both the wound and the strange, haunting fragrance that rises from it.

RM: How many iterations did your translation go in working on this specific text. What has been the most challenging aspect of this translation? What makes this book different from other works that you have translated? Take us through your approach and process of translation.

ANK: This translation went through several iterations, perhaps three or four drafts. Each stage wasn’t about correcting language as much as deepening my understanding of tone, texture and silence. The novel resists smoothness. It demands to be read and translated in fragments, pauses, and echoes. So, I kept returning to it, letting the English find its own rhythm without erasing the Urdu’s haunted music, as far as I could do. The most challenging aspect was to hold on to the tension between beauty and decay. The prose often veers between the lyrical and the grotesque, and it’s easy for one to overpower the other in translation. Preserving that balance, where disgust carries grace, and silence holds meaning was perhaps the toughest part. What makes this book different from other works I’ve translated is its atmosphere of delirium. It’s less a story and more an experience of consciousness collapsing under its own weight. My process therefore involved a kind of surrender – reading aloud, listening to cadences, allowing the English to sound slightly foreign because the text itself is foreign to sanity. Translation, in this case, became less about fidelity and more about resonance, about carrying across not just words, but a condition of being.

RM: How important it is to read to translate? What kind of reading has helped your own translation?

ANK: Reading is the very soul of translation. One cannot translate without first being an attentive, empathetic and restlessly curious reader. To translate well is to read on multiple levels at once not only the words on the pages but the silences that frame them, and the world from which the text emerged – its history, culture and unspoken traumas, and the world it yearns to address. This deep, multidimensional reading cultivates an ear for the intangible, the cadence of a thought, the shadow of irony and the breath of a sentence. These are the qualities that defy technical manuals and must be intuitively felt. Consequently, reading provided me with the essential instrument – an inner ear. By listening deeply, we learn to hear the voice we’re meant to carry across, and translation becomes the art of inhabiting another consciousness and letting our own language tremble in authentic response.

RM: How do you select the works that you want to translate? What future projects do you have in your pipeline?

ANK: To me, this vocation is not a matter of choice so much as being chosen. I don’t so much select works to translate as feel selected by them. Khalid Jawed gave me this novel, its title and story began to haunt me. The world and its voice lingered in my mind, the silences echoed through my days. And that persistent resonance felt like a summons. So, I undertook the translation. I was drawn to it because it unsettles our comforts and maps the fractures that run through history, memory and the self. Its language offered a deliberate resistance; only through that friction does translation become a meaningful, transformative struggle. I’m inclined towards texts with moral and aesthetic complexity, speaking of decay and disgust, existential longing and a quiet endurance amid collective collapse. To translate such a work is an act of recovery: rescuing a vital consciousness from the brink of oblivion and giving it the chance of another life. My forthcoming works include my English translation of S. M. Ashraf’s Aakhri Sawariyaan as The Last Rides and my Urdu translation of Cyrus Mistry’s Chronicle of a Corpse Bearer as Ek Murda Dhoney Waley Ki Kahani.

A Naseeb Khan is a bilingual poet, translator and author. Recipient of the Delhi Urdu Academy Award, his poems have featured in multiple Urdu anthologies including Rip Not the Sore and Naee Nazm Naya Safar. As a translator, he has several credits to his name, including a monograph on Moin Ahsan Jazbi, and Ghalib’s couplets included in the Evolution of Ghalib.