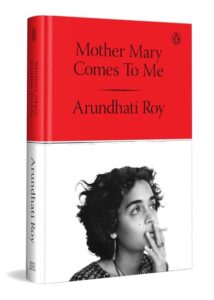

Excerpt Mother Mary Comes to Me

Image Courtesy of Penguin Random House India

Gangster

She chose September, that most excellent month, to make her move. The monsoon had receded, leaving Kerala gleaming like an emerald strip between the mountains and the sea. As the plane banked to land, and the earth rose to greet us, I couldn’t believe that topography could cause such palpable, physical pain. I had never known that beloved landscape, never imagined it, never evoked it, without her being part of it. I couldn’t think of those hills and trees, the green rivers, the shrinking, cemented-over rice fields with giant billboards rising out of them advertising awful wedding saris and even worse jewelry, without thinking of her. She was woven through it all, taller in my mind than any billboard, more perilous than any river in spate, more relentless than the rain, more present than the sea itself. How could this have happened? How? She checked out with no advance notice. Typically unpredictable.

The church didn’t want her. She didn’t want the church. (There was savage history there, nothing to do with God.) So given her standing in our town, and given our town, we had to fashion a fitting funeral for her. The local papers reported her passing on their front pages, most national papers mentioned it, too. The internet lit up with an outpouring of love from generations of students who had studied in the school she founded, whose lives she had transformed, and from others who knew of the legendary legal battle she had waged and won for equal inheritance rights for Christian women in Kerala. The deluge of obituaries made it even more crucial that we do the right thing and send her on the way she deserved. But what was that right thing? Fortunately, on the day she died the school was closed and the children had gone home. The campus was ours. It was a huge relief. Perhaps she had planned that, too.

Conversations about her death and its consequences for us, especially me, had begun when I was three years old. She was thirty then, debilitated by asthma, dead broke (her only asset was a bachelor’s degree in education), and she had just walked out on her husband—my father, I should say, although somehow that comes out sounding strange. She was almost eighty-nine when she died, so we had sixty years to discuss her imminent death and her latest will and testament, which, given her preoccupation with inheritance and wills, she rewrote almost every other week. The number of false alarms, close shaves, and great escapes that she racked up would have given Houdini pause for thought. They lulled us into a sort of catastrophe complacency. I truly believed she would outlive me. When she didn’t, I was wrecked, heart-smashed. I am puzzled and more than a little ashamed by the intensity of my response.

Excerpted with permission from Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy published by Penguin Random House India 2025

Arundhati Roy is the author of the novels The God of Small Things, which won the Booker Prize in 1997, and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2017. Her non-fiction includes My Seditious Heart, Azadi and, most recently, her memoir Mother Mary Comes to Me. She lives in Delhi.