Review: Meet the Savarnas |Ravikant Kisana

By Eram Asrar

“And truly, all I ever wanted at that stage of my life was to escape the gravitational orbit of the milieu my life was circulating around.” Call it an epigraph for a country that, in the 2000s, was promised a quick ascent: MBAs, liberalisation, and meritocracy on tap. The myth stalled, in part, because old hierarchies took on new clothes.Today the urban privileged don’t practice ‘untouchability’; they practice monopolies of taste, closed networks, and complacent mediocrity disguised as merit.

The book is simple: it dissects an elite cohort and maps how caste seeps into every ordinary thing. It begins by naming the savarna, that historically privileged urban class and then proceeds, chapter by chapter, to show how their values, habits and networks quietly reproduce inequality. The book’s central provocation is simple and elegant. The elite do not stand on a glass ceiling; they float on a glass floor. Above it, light and opportunity flick on. Below it, millions labour in the dark. The rhetoric of meritocracy and liberalism is exposed as varnish. Networks, not just merits, open doors. Weddings, schools, start-up pipelines, editorial rooms, and matrimonial WhatsApp chains become sites where privilege is distributed and defended. The narrative traces the savarnas’ arc: post-1990s enthusiasm for global commerce and MBAs; the taste for cosmopolitan culture; then a sluggish return to cultural conservatism and comfort. The irony is clinical. They call themselves modern. Their institutions keep working exactly as they always did. The book shows this with crisp ethnographic vignettes, clipped historical context and a steady accumulation of examples that make the central claim unavoidable: the generation that promised to “make India superpower by 2020” ended up embedded in the very scaffolding that keeps most people from rising.

Classrooms still sell the myth that varna was just a fair division of labour, later “corrupted.” This story cleanses a brutal system, recasting inequality as order, and oppression as pragmatism.

The reality is harsher: whole communities were cast out as avarna, forced into filth and branded untouchable, while dwij savarnas flaunted the sacred thread as proof of purity. Servitude was made hereditary, chained to salvation itself. To resist meant not just punishment in life, but damnation beyond it.

Dr. Ravikant takes on the unlovely task of naming the savarna and the question here is neat: how did caste elites meet modernity, and why did their self-assured scripts fail to deliver the promised prosperity? The title does what it says. Dr. Ravikant takes that small basket of concession and deftly turns it around to show the other side: reservation, when poorly implemented, can leave SC/ST/OBC students feeling like ill-fitting keys in an alien lock, forced to leave, to endure isolation, or to shoulder burdens that sometimes end in tragedy.

The narrative follows their arc: 1990s globalisation, white-collar ascents, a glossy cosmopolitan taste, and then a slow gharwapasi to cultural conservatism. Meanwhile, the numbers below are the structural reality, a vast majority live under different rules, even as savarna networks quietly commandeer resources and planning prerogatives. In short: their achievements are often scaffolded by exclusions they barely acknowledge.

He brilliantly inverts the familiar “glass ceiling” trope. Instead of a ceiling, he hands us a basement view: millions crowded below, while savarnas stroll above on a polished glass floor, flicking on and off the switches of the whole house. Light, water, jobs, all wired to their comfort. What struck me most while reading was how uncomfortably familiar this image felt. I’ve sat in classrooms where a single surname announced more opportunities than a full CV, and I’ve watched group discussions where English fluency was confused with brilliance. That is the glass floor at work: invisible to those walking on it, blindingly obvious to those pressed against it from below.

Dr. Ravikant pushes further by introducing the savarna gaze “photochromic”: the hotter the fire burns below, the darker the glass becomes. Translation: privilege adapts. When caste violence makes headlines, the privileged simply dim the lights. In one chapter, he even suggests that keeping people “in their place” is less a conscious choice than a cultural dharma, a script rehearsed so often it feels instinctive. It’s a sharp claim, but the evidence lands: from parental ultimatums over inter-caste marriages to Bollywood romances that reassure audiences that true love blossoms only once the “family” (read: caste privilege) gives its benediction. Even DDLJ, that sacred cow of Indian cinema, emerges here less as a love story than as a parable of patriarchal comfort.

The brilliance of the book, though, is more in the performance than in the argument. Its wit is surgical. He peels back layers of their self-image to show how caste operates as an invisible scaffold under their feet. At one point, one can find themselves laughing at a line about tech-bro entitlement and then immediately shutting the book to sit with the discomfort it provoked. That is the rhythm: satire as scalpel. Humor becomes the method through which he makes the absurdity of privilege legible. Reading it felt less like ploughing through an academic treatise and more like sparring with a contrarian friend in the campus café, the kind who drops a bitter truth, watches you wince, and then cracks a joke so sharp you can’t help but laugh.

One of the book’s choicest amusements is its portrait of savarna mediocrity, comic if it weren’t so tragic. Once upon a time, popular culture poked fun at the meek office babu; today we have his shinier cousin, the MBA-wielding savarna millennial, armed with PowerPoints and a LinkedIn premium subscription. Dr Ravikant observes that while “vast masses of excluded SC/ST/OBCs heave and expand in the shadows, corporate India struggles with its stagnation and mediocrity, in large measure due to the millennial savarna MBAs.” Their battle cry of the early 2000s, karo duniya mutthi mein (seize the world), has fizzled into the muted whimper of quarterly reports and memes about Monday mornings. When ambition sags, regression beckons. Instead of building futures, many retreat into Brahmanical orthodoxy, conservatism wrapped in a soft, apologetic tone, nostalgia polished as virtue. Their cultural imagination, the author insists, is an oxymoron: ambitious in rhetoric, timid in vision, endlessly recycling myths of a golden India that somehow never arrives.

He dissects how the neoliberal boom both shaped and was shaped by caste privilege. The 1990s promised IITs, IIMs, and IT dreams; what arrived was an “MBA revolution” built on the savarna glass floor. Reservation debates were hushed. Merit was paraded as gospel. Corporate India cheered itself while ignoring who was left outside. For those below, little changed: jobs, land, housing, education remained locked behind inherited networks and high investment. Even when marginalized students entered, many felt “savarna-washed,” taught to blame caste politics instead of the system. Silence, author notes, became its own weapon. Every pause, every hesitation by the marginalized was noted, stored, and returned as petty structural vengeance.

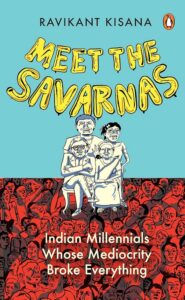

What keeps this from reading like a grim policy paper is the style, razor-sharp, witty, and illustrated even on the cover. A cheery savarna family lounges above a shimmering glass floor, their mockery etched in cartoon smiles, while below a sea of red faces glare upward, equal parts angry and exhausted. The image condenses the argument: privilege has perfected the art of looking down without ever seeing. And the book’s subtitle: Indian Millennials Whose Mediocrity Broke Everything, makes clear the aim and purpose of the book.

Even the most private domains, love, sex, marriage are not free from the savarna script. Caste seeps into intimacy, turning desire into a patrolled border. Inter-caste marriages are cast as betrayal; endogamy is enforced with persuasion at best, and at worst, with the blunt force of “honour killing,” where young lovers are punished for daring to cross lines. Even when modern savarnas flirt across caste, the real negotiation begins at the marriage threshold, where the “family” (that polite stand-in for caste authority) presses its veto. The result: intimacy folded neatly back into hierarchy. Affection is allowed, but only inside caste borders, a reminder that even in bedrooms and wedding halls, privilege decides who belongs.

The book also skewers the masquerade of modern dating. Apps promise cosmopolitan love, swipe-left, swipe-right, caste-blind freedom. Yet, the performance collapses at the altar. Many young savarnas insist they “don’t even know their caste properly,” but the moment a marriage dossier is opened, a checklist emerges: the bride must be “from the right family,” and “culturally aligned.”

Desire may masquerade as modern, but matrimony remains ancient. Even the grammar of apps betrays it: dating is play, marriage is caste-endorsed permanence. As the author notes, “keeping people in their place… is their very dharma,” and in intimacy that dharma is enforced with quiet persistence through family vetoes, honour killings, or even algorithmic filters that decide who counts as “eligible.” The logic doesn’t stop at savarnas. Dominant castes lower down the ladder police the same lines, wielding power over those beneath them. It is a crude inheritance, a cruelty sanctified by our “golden texts,” where love must always bow to lineage. Cupid here doesn’t shoot arrows; he carries a caste certificate, stamped and notarised by tradition.

And this same script extends to campuses. While JNU, Jamia, and Aligarh have long been crucibles of protest with marches, slogans, and the occasional police baton charge their elite private cousins stayed eerily hushed. In manicured campuses, savarna students fluent in “global citizenship” and TED-talk jargon somehow lost their taste for dissent.

Does Meet the Savarnas deliver on its promise? For the most part, yes. The title pledges a portrait of the upper-caste class, and what we get is a full-length close-up: history, anecdotes, data, memes, even Netflix references. It teaches as much as it persuades, population figures, campus cultures, startup lore all repurposed to show how deeply caste shapes “success.” And it provokes, sometimes brutally; I often felt winded, as though a chapter had punched me squarely in the ribs. The subtitle’s claim that savarna mediocrity “broke everything” may sound like hyperbole, but the evidence piles up until the provocation feels earned.

The message, though rooted in caste, speaks beyond it. The Bhakti poets once insisted devotion leveled all hierarchies; Soyarabai declared untouchability meaningless before the soul. If our tradition railed so fiercely against prejudice, why does modern India shrug it off in classrooms, temples, and bedrooms alike? This book reminds us that caste doesn’t disappear in theory, it lives in practice. To ignore it now would be to betray the very ideals that once made Bhakti radical.

Its strengths are obvious. Dr Ravikant writes with unusual clarity; his “glass floor” metaphor is the kind of image that sticks. He skewers corporate jargon, startup smugness, and campus hypocrisy with equal ease, blending academic analysis with meme-age slang. Each chapter builds logically, from economics to intimacy, but the language keeps it sharp, never plodding. That balance, scholarly structure with irreverent wit makes the book readable without sacrificing rigor.

Of course, no book is flawless. Some readers will crave more voices from the marginalized side. But the choice to stick with savarnas themselves is deliberate: it forces the privileged to see themselves, unflatteringly, in the mirror. The repetition, savarna obliviousness hammered in chapter after chapter might feel wearying, yet that fatigue is the point. Privilege is exhausting to witness because it’s exhausting to live under. And yes, the tone can be caustic, even cruel. But sugarcoating caste would only blunt the edge, and this book thrives on being sharp.

Most importantly, it speaks to its audience. The author writes in the idioms of millennials and Gen Z: podcasts, TikTok jokes, meme wars, and startup speak. Well considering he is a professor but here it’s a peer talking back in your own language. That immediacy makes the critique land harder. Twenty-somethings will laugh, flinch, and recognize themselves; older readers may bristle, but that’s collateral damage. Either way, the book respects its readers by never pandering, never softening the blow.

So who should read this? Anyone invested in India’s present or its future. If you are savarna, it will demand humility about the glass floor beneath you. If you are not, it gives you a vocabulary to decode the entitlement you encounter daily. And if you are outside India, it’s an education in the silent architecture shaping a billion lives.

In short, Meet the Savarnas is a provocation and necessary: it insists that caste seeps everywhere, in offices, in bedrooms, in WhatsApp groups and leaves you questioning what you thought was “merit.” It is important to be educated on topics that are considered outdated yet still is an ongoing trend secretly purring from the bag. By the last page, you’ll be bruised, sharper, maybe even embarrassed. But you’ll also be wiser. And in that unease, I found myself circling back to where I began: “all I ever wanted at that stage of my life was to escape the gravitational orbit of the milieu my life was circulating around.” Reading this made that orbit visible and escaping it, or at least naming it, feels like the first step.

Ravikant Kisana is currently the Associate Dean & Associate Professor at Woxsen University, Hyderabad. His expertise lies in Cultural Studies and ethnographic research grounded in Critical Caste Studies. He also podcasts and performs live under the moniker of ‘Buffalo Intellectual’.

Subscribe to our newsletter To Recieve Updates